Venus

- Date de création

- 4th century?

- Material

- Marble

- Dimensions

- H. 77,5 x l. 28,5 x P. 20 (cm)

- Inventory number

- Ra 151-Ra 114

- Photo credits

- Daniel Martin

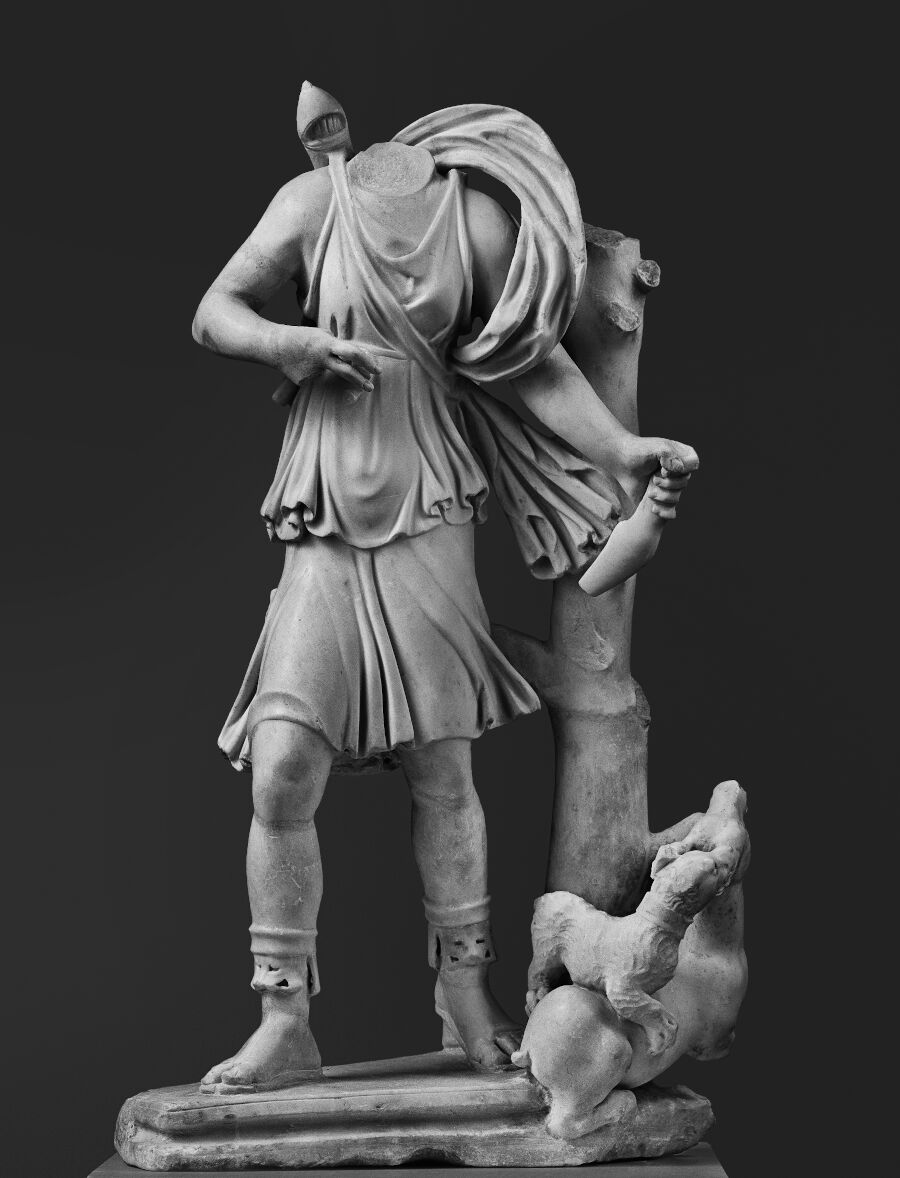

While many of the works found during the excavations of the villa were immediately given special attention and exhibited, some were relegated to the reserves. The fact that some works were not put on display can be explained. Firstly, it is important to mention the uncertainties and questions regarding the origin of a number of these sculptures: the vagueness of inventories, as well as 19th century sources, have often led curators to remain cautious and reserved when it comes to attributing certain marble items to the villa. And of course there were aesthetic biases, which resulted in some works being excluded. These obviously suffered from preconceptions based on the history of forms. They were attributed to less competent workshops, too often compared to more classical statuary, and therefore sentenced to a life in exile. And for each curator confronted with a lack of space in the exhibition areas, this sentence is validated by the obligation to make a drastic selection. Typically, this statue of Venus was no exception, as it embodies, better than any other, a type of work that is easily overlooked.

Crowned with a tiara, the figure is characterised by an unusual slimness and proportions that immediately draw one’s attention. Its elongated forms and flat buttocks and torso certainly set the work apart. When the two fragments that make up her body were discovered in 1890, Villa Chiragan was undergoing its third major official excavation campaign directed by Albert Lebègue, professor at the Faculty of Literature in Toulouse G. Perrot, « Rapport sur les fouilles de Martres, » Revue Archéologique, 18, 1891, pp. 56–73, en partic. p. 415.. The break was just above the umbilical region, and both parts were therefore stuck back together again. The right hand holding a strand of hair is said to have been unearthed at the same time É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, 2. Aquitaine, Paris, 1908, no 903.. The head, probably discovered during the first half of the century, and already kept among the collections of the museum in Toulouse, was not reunited with its body until 1948 by Paul Mesplé P. Mesplé, « Raccords de marbres antiques, » La Revue des Musées de France, July, 1948, en partic. p. 156.. Émile Espérandieu erroneously attributed his discovery to the excavations led by Léon Joulin in 1897-1899 É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, 2. Aquitaine, Paris, 1908, no 905.. This head may have been mentioned on the first page, now unfortunately missing, of the handwritten notebook corresponding to the discoveries of the 19th and 20th September 1826 J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : Époque julio-claudienne, 1.1 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2005, p. 35..

Description

This Venus is entirely naked. The weight of the body is resting on the left leg. Her head is turned to the left, and slightly bent forward. The bust is particularly slender, the breasts small, and the pelvis, which is wide but very short, contrasts with the upper part of the body. The neck, finally, which is long and thin when viewed from the front, appears thicker when viewed from the left, looking more like a cylinder whose connection with the face (which is delicate and clearly oval in shape) appears less natural. On her head she wears a smooth tiara. Two strands of hair have escaped from her chignon, one straying over her left shoulder and the other over her right arm. They were probably damaged and restored using stucco, as the marks made at shoulder blade level with a point tend to prove, as these could correspond to so many pit marks made to facilitate the adherence of the stucco. Five points of contact, four at the top of the right thigh, and another in the lower abdominal area, show that the left hand was positioned in front of the pubic area. On the left thigh, at the level of the vastus lateralis muscle, a tenon indicates the position formerly occupied by the element that once ensured the statue’s stability. Three points of contact on the hip probably correspond to the end of the caudal fin of a dolphin, endowed, according to the ancient iconographic tradition regarding this animal, with several appendages. The cetacean’s head probably rested directly on a moulded plinth, a block shared by the goddess and her seafaring companion.

A famous model…

This work has been said to be a very late variant of the Knidian Aphrodite, an illustrious and recurring model created in the workshop of Praxiteles around 360 BC A. Pasquier, J.-L. Martinez, Praxitèle. Exhibition, Musée du Louvre, Paris, 23 March - 18 June 2007, Paris, 2007, pp. 172-195.. The original, made of marble, and intended as an ode to the beauty of the beloved Phryne, whose radiant silhouette could but suit the goddess of Cyprus, is now lost. The Roman version at the Vatican Museums, known as the « Venus of the Belvedere » (inv. 4260), is said to adhere to the same design. But this body, whose total and radiant nudity did not require superfluous finery, referred to a bodily beauty hitherto limited only to the male anatomy. It generated an infinite number of copies and all kinds of by-products, as evidenced by the variants attributed to oriental workshops. Driven by a constantly growing market of collectors, between the end of the 2nd century BC and the course of the following century, the sculptors of Rhodes or Alexandria designed a medium-sized statuary, often full of references and allusions to the masterpieces produced during the classical period. Such is the case of a Rhodian Aphrodite Anadyomene in particular, whose body, when seen from the sides, is characterised by its very slim frame F. Queyrel, La sculpture hellénistique , Tome 1 : Formes, thèmes et fonctions (La sculpture grecque , 3; Les manuels d’art et d’archéologie antiques), Paris, 2016, p. 95-96, fig. 77 ; Ó. Palaggiá, M.D. Fullerton, « Atticism, Classicism and the Origins of Neo-Attic Sculpture, » W.D.E. Coulson, American school of classical studies at Athens (eds.), Regional Schools in Hellenistic Sculpture : Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, March 15-17, 1996 (Oxbow Monograph), Oxford, 1998, pp. 93–99, pp. 94-99..

It is widely known that the reproduction industry and Western commercial outlets were to prove fundamental in passing on mythological references from the ancient Greek civilization to rich buyers eager to collect and display them around their homes and even in associative and commercial premises. The decorative statuary designed especially for them was not devoid of sensuality and even humorous details, as well as delightful anecdotal references (Pan and Aphrodite commissioned by the Beiruti merchants’ association of Delos, and now kept at the National Museum of Athens, is a good example of this).

Some five hundred years later, the Venus discovered at Villa Chiragan is the natural heiress of such compositions. The left hand held in front of the pubic area, a gesture intended to convey her modesty but also to draw attention to the vigorous fertility of this daughter of Uranus, maintains a direct link with Praxiteles’ masterpiece. It is indeed reminiscent of the sculpture acquired by the island of Knidos, to which the leftward position of the head and gaze also refer A. Corso, The Art of Praxiteles, II : The Mature Years (Studia Archeologica), Rome, 2007, pp. 9-22.. With this statue of Venus however, it is the left hand that is held in front of the genitals. This inversion can be explained by the aesthetic variations, of which there are very few considering the number of centuries that have gone by, that nevertheless act as so many filters between the original work and the works produced during the imperial period. The most famous of these derivatives, which is characteristic of this inverted gesture, is of the pudica type, also known as the Venus de’ Medici. It is also worth noting the position of the right arm, which is also broken, but still bears a stray strand of hair. Her arm was vigorously held aloft in a gestures reminiscent of the Aphrodite Anadyomene, a creation of the painter Apelles of Kos, if we are to believe Athenaeus Athénée, Deipnosophistes, 3rd century, XIII, 59.. She is also said to have been inspired by the bewitching courtesan Phryne Athénée, Deipnosophistes, 3rd century, XIII, 59..

Exported to Rome following the Roman conquests at the end of the Republic, and exhibited on the orders of Augustus in the temple of Caesar according to Pliny, Apelles’s tablet (pinax) was severely damaged before being reproduced during the reign of Nero Pline l’Ancien, Histoire naturelle, 77 (circa), 36.28.. In the same way that we imagine that Praxiteles’ Venus is about to enter the water A. Corso, The Art of Praxiteles, II : The Mature Years (Studia Archeologica), Rome, 2007, p. 14., we can easily picture that the anadyomene is emerging from it, gathering her wet hair with both hands on either side of her head as she does, to wring the water from it. This gesture would be reminiscent of that of the athlete tying his headband, a famous marble statue known as Diadumenos created by Polyclitus C. Rolley, La sculpture grecque , 2 : La période classique (Les manuels d’art et d’archéologie antique), Paris, 1999, pp. 35-36.. This in the round anadyomene, a female transposition of the work attributed to Polykleitos, was probably created in the fruitful context of Alexandrian workshops during the first century BC. It emphasises and conveys the Greek concept of charis (grace) of this female body with its distinctive curves, full lines, wide hips and small, firm breasts. Like her pubic hair, the hair on her head is shown to symbolise the fertile power of women, as well as their seductive power and strong urge to please L. Bodiou et al., « La chevelure d’Aphrodite et la magie amoureuse, » L’expression des corps : gestes, attitudes, regards dans l’iconographie antique (Cahiers d’histoire du corps antique), Rennes, 2006, p. 187.. The twisting of the wet hair would appear to refer to a different form of bondage: that of bound breasts, a symbolic gesture that stems from a long tradition in the Eastern world L.M. De Matteis, « Sull’Afrodite anadyomene, » Cháris Chaíre, Athens, 2004, pp. 125–133, p. 129..

…but a model that has been readapted

Although the system of ideal proportions adopted for the representation of Venus during the classical period depended on a canon that gave pride of place to round, robust forms, there is nothing of the kind in our sculpture. The fact that this work was relegated to the museum’s reserves, and the unjustified indifference towards it, could be explained as we have said, by aesthetic differences when compared to the prototype: unattractive proportions, the unconventional slenderness of her thorax, the flatness of the whole body characterised by the unformed buttocks that extend her already unshapely back, and finally the neck, which resembles a long cylinder when viewed from the front, and is too thick when viewed from the side. When seen from the left, its very abrupt and seamless connection with the face is unsightly.

While Venus’s body appears particularly flat and slender when viewed from behind, and even more so when seen from a three-quarter angle, it may well be that this elongation and deformation is based on a particular taste and, obviously a style introduced in certain oriental workshops during the last centuries of antiquity L.M. Stirling, « Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors : Scuptural Decoration in Late-Antique Aquitania, » La Civilisation Urbaine de l’Antiquité Tardive Dans Le Sud-Ouest de La Gaule. Actes Du Ille Colloque Aquitania et Des XVIe Journées d’Archéologie Mérovingienne Toulouse 23-24 Juin 1995, Bordeaux, 1996 (2), pp. 209–230, p. 215 ; L.M. Stirling, « Divinities and Heroes in the Age of Ausonius : A Late-Antique Villa and Sculptural Collection at Saint-Georges-de-Montagne (Gironde), » Revue Archéologique, 1, 1996 (1), pp. 103–143, en partic. pp. 103-143.. To understand this, we need to refer to a group of statues from the Cyrene Sculpture Museum L.I.M.C., Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. V. 1, Herakles - Kenchrias, Zürich ; Munich, 1990, II, 1, 157, 69 ; II, 2, 161, fig. 69., which were nevertheless probably produced at an earlier date, as well as a  series of medium-sized statues kept in Dresden (of the « Rospigliosi-Latran » type), L.I.M.C., Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. V. 1, Herakles - Kenchrias, Zürich ; Munich, 1990, II, 1, 646, 251 - 283.), whose very slim torsos associated with solid lower limbs, border on the strange, and allow for a graphic rather than a realistic representation of the body M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, pl. 56-57.. Some other elements betray this aesthetic trend, such as the S-shaped curl on the forehead, the slightly abrupt transitions of the outlines of the face, the eyebrows that form an acute angle, and the deep furrows that separate the wavy strands of hair in a rather artificial way. These characteristics allow us to link together a series of works, the late dating of which was appropriately justified by Marianne Bergmann: Hygieia of Rhodes M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, 51, pl. 49-1., female heads from Dijon M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, p. 45, p. 47, pl. 55-2, 56-2. and Chiragan M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, p. 54, pl. 55-3.4, 56-3., Apollo from Saint-Georges-de-Montagne, M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, p. 54, pl. 55-1, 56-4. as well as a large female portrait at the Musei capitolini M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, 61-63 ; K.T. Erim, Aphrodisias : City of Venus Aphrodite, London, 1986 ; M. Floriani Squarciapino, La Scuola di Afrodisia : Studi e materiali del Museo dell’Impero romano. 3, Rome, 1943..

series of medium-sized statues kept in Dresden (of the « Rospigliosi-Latran » type), L.I.M.C., Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. V. 1, Herakles - Kenchrias, Zürich ; Munich, 1990, II, 1, 646, 251 - 283.), whose very slim torsos associated with solid lower limbs, border on the strange, and allow for a graphic rather than a realistic representation of the body M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, pl. 56-57.. Some other elements betray this aesthetic trend, such as the S-shaped curl on the forehead, the slightly abrupt transitions of the outlines of the face, the eyebrows that form an acute angle, and the deep furrows that separate the wavy strands of hair in a rather artificial way. These characteristics allow us to link together a series of works, the late dating of which was appropriately justified by Marianne Bergmann: Hygieia of Rhodes M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, 51, pl. 49-1., female heads from Dijon M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, p. 45, p. 47, pl. 55-2, 56-2. and Chiragan M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, p. 54, pl. 55-3.4, 56-3., Apollo from Saint-Georges-de-Montagne, M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, p. 54, pl. 55-1, 56-4. as well as a large female portrait at the Musei capitolini M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, 61-63 ; K.T. Erim, Aphrodisias : City of Venus Aphrodite, London, 1986 ; M. Floriani Squarciapino, La Scuola di Afrodisia : Studi e materiali del Museo dell’Impero romano. 3, Rome, 1943..

Venus is apparently, and by far, the most popular mythological figure in villae in activity during this period, followed by representations of satyrs, which evoked the other dominant god: Dionysus C. Videbech, « Private Collections of Sculpture in Late Antiquity : An Overview of the Form, Function, and Tradition, » J. Fejfer, M. Moltesen, A. Rathje (eds.), Tradition : Transmission of Culture in the Ancient World (Acta Hyperborea), Copenhagen, 2015, pp. 451–480, p. 473.. Characterised as it is by its hybrid gestures, Chiragan’s sculpture therefore belongs to a later period, during which such small and medium sized statues flourished, and were distributed in entrances, dining rooms and baths, and of course gardens, some in private spheres, and others in semi-public and even public areas.

P. Capus

Bibliography

- Bergmann 1999 M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden.

- Capus 2020 P. Capus, « La minceur de Vénus : Une statue oubliée de la villa de Chiragan, » Maigreur et minceur dans les sociétés anciennes. Grèce, Orient, Rome (Scripta Antiqua), Toulouse, PLH-CRATA, Université de Toulouse Jean-Jaurès, pp. p. 163–170.

- Cazes, Guilbaut, Martinaud 2005 D. Cazes, J.-E. Guilbaut, M. Martinaud, « Martres-Tolosane, » Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles (Midi-Pyrénées), Service Régional de l’Archéologie (eds.), Bilan scientifique de la région Midi-Pyrénées: 2001, Paris, p. 74.

- Espérandieu 1908 É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, 2. Aquitaine, Paris. no 903, 905

- Joulin 1901 L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris. p. 95-96, pl. X, no 123 D, no 128 E

- Mesplé 1948 P. Mesplé, « Raccords de marbres antiques, » La Revue des Musées de France, July. p. 156

- Perrot 1891 G. Perrot, « Rapport sur les fouilles de Martres, » Revue Archéologique, 18, pp. 56–73. p. 64

- Rachou 1912 H. Rachou, Catalogue des collections de sculpture et d’épigraphie du musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. no 114, no 151

- Stirling 1996 (2) L.M. Stirling, « Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors : Scuptural Decoration in Late-Antique Aquitania, » La Civilisation Urbaine de l’Antiquité Tardive Dans Le Sud-Ouest de La Gaule. Actes Du Ille Colloque Aquitania et Des XVIe Journées d’Archéologie Mérovingienne Toulouse 23-24 Juin 1995, Bordeaux, pp. 209–230.

- Stirling 2005 L.M. Stirling, The Learned Collector : Mythological Statuettes and Classical Taste in Late Antique Gaul, Ann Arbor.

- Musée Saint-Raymond 2020 Musée Saint-Raymond, Wisigoths : rois de Toulouse. Exhibition, Musée Saint-Raymond, Toulouse, 27 February - 27 December 2020, Toulouse. p. 169-179 (notice P. Capus)

- Musée Saint-Raymond 2010 Musée Saint-Raymond, Dieux du ciel ! L’irruption de l’espace. Exhibition, Musée Saint-Raymond, Toulouse, 2010, Toulouse. p. 49

- Musée Saint-Raymond 2019 Musée Saint-Raymond, Age of Classics ! L’Antiquité dans la culture pop. Exhibition, Musée Saint-Raymond, Toulouse, 22 February - 22 September 2019, Toulouse. repr. p. 225

To cite this notice

Capus P., "Venus", in The sculptures of the roman villa of Chiragan, Toulouse, 2019, online <https://villachiragan.saintraymond.toulouse.fr/en/ark:/87276/a_ra_151_ra_114>.