How can we trace the history of such a group of constructions? How did it evolve? What did it look like? Although our only documentary source remains the priceless sum of information published in 1901 by Léon Joulin, the last person to have excavated the site, the sculptures retrieved from the villa represent the only material evidence, apart from a few rare objects, that we have had to work on. Yet this alone was striking proof of the site’s prestige. Although it is difficult to explain the presence of such a large collection of marble sculptures in a single location, the types and styles, and even a certain predisposition for particular themes can nevertheless help to identify different periods of occupation. Because of the apparent chronological isolation of a beautiful and rare female head, that dates back to the late 4th century or early 5th century, we could only speculate on the very late occupation, or even re-occupation, of the site owing to a lack of additional archaeological material. And it was difficult to imagine an earlier settlement based on dates that go no further back than the 3rd century D. Cazes et al., Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris, 1999, p. 83-117 et 147.. The studies conducted by Marianne Bergmann M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999., Niels Hannestad N. Hannestad, Tradition in Late Antique Sculpture : Conservation, Modernization, Production (Acta Jutlandica. Humanities Series), Aarhus, 1994, pp. 294-295 ; N. Hannestad, « Late Antique Mythological Sculpture - In Search of a Chronology, » F.A. Bauer, C. Witschel, Ludwig-Maximilians Universität (eds.), Statuen in Der Spätantike, Wiesbaden, Germany, 2007, pp. 273–305 ; N. Hannestad, « The Classical Tradition in Late Roman Sculpture, » Akten Des XIII Internationalen Kongresses Für Klassische Archäologie, Berlin, 1988, Mainz, 1990. and Lea Stirling L.M. Stirling, « Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors : Scuptural Decoration in Late-Antique Aquitania, » La Civilisation Urbaine de l’Antiquité Tardive Dans Le Sud-Ouest de La Gaule. Actes Du Ille Colloque Aquitania et Des XVIe Journées d’Archéologie Mérovingienne Toulouse 23-24 Juin 1995, Bordeaux, 1996 (2), pp. 209–230, pp. 209-230 ; L.M. Stirling, The Learned Collector : Mythological Statuettes and Classical Taste in Late Antique Gaul, Ann Arbor, 2005. on Roman sculpture during Late Antiquity have resulted in the revision of certain chronological data, in particular.

It is important to stress that the different stages of the villa, as detailed by Léon Joulin, cannot be confirmed unless conscientiously planned excavations are resumed on a large scale. In the meantime, an impressive collection of sculptures carved from Saint-Béat marble, which represents a substantial percentage of the statuary extracted from the villa, now gives us a better idea of the timeline of these decorative elements.

Marble from the Pyrenees

Some of the assumptions that were made about the sculpted ensemble unearthed on the site of the villa can now be substantiated thanks to an understanding of the marbles that were used to make them D. Attanasio, M. Bruno, W. Prochaska, « The Marbles of the Roman Villa of Chiragan at Martres-Tolosane (Gallia Narbonensis), » Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1, 2016, pp. 169–200.. With regard to the large group of portraits, the tests have proved particularly edifying, showing that 80% of them were made from oriental marble. These same studies also confirmed Léon Joulin’s postulate concerning certain later mythological works and some probably contemporary portraits, namely that local marble from the quarries in Saint-Béat had been used.

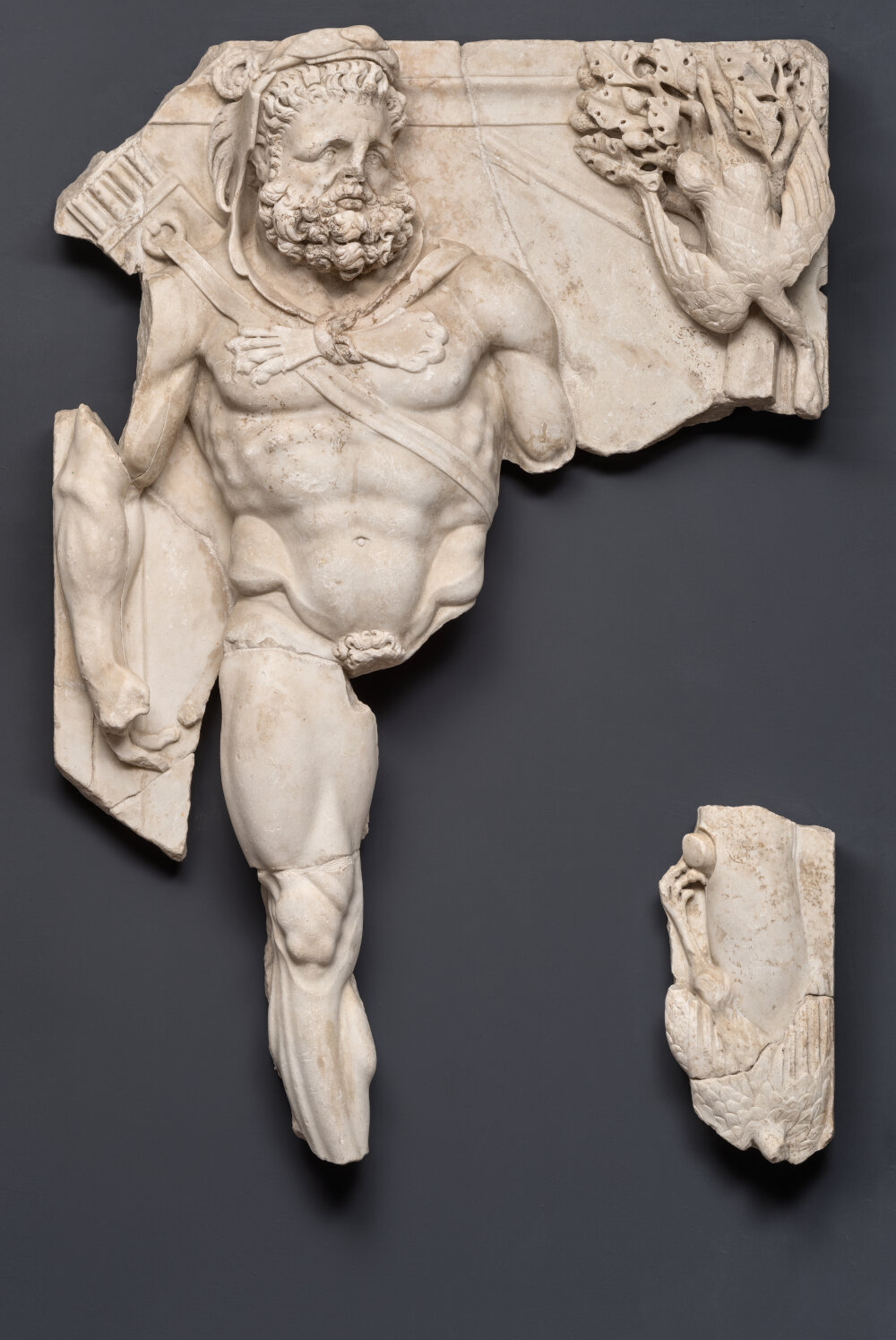

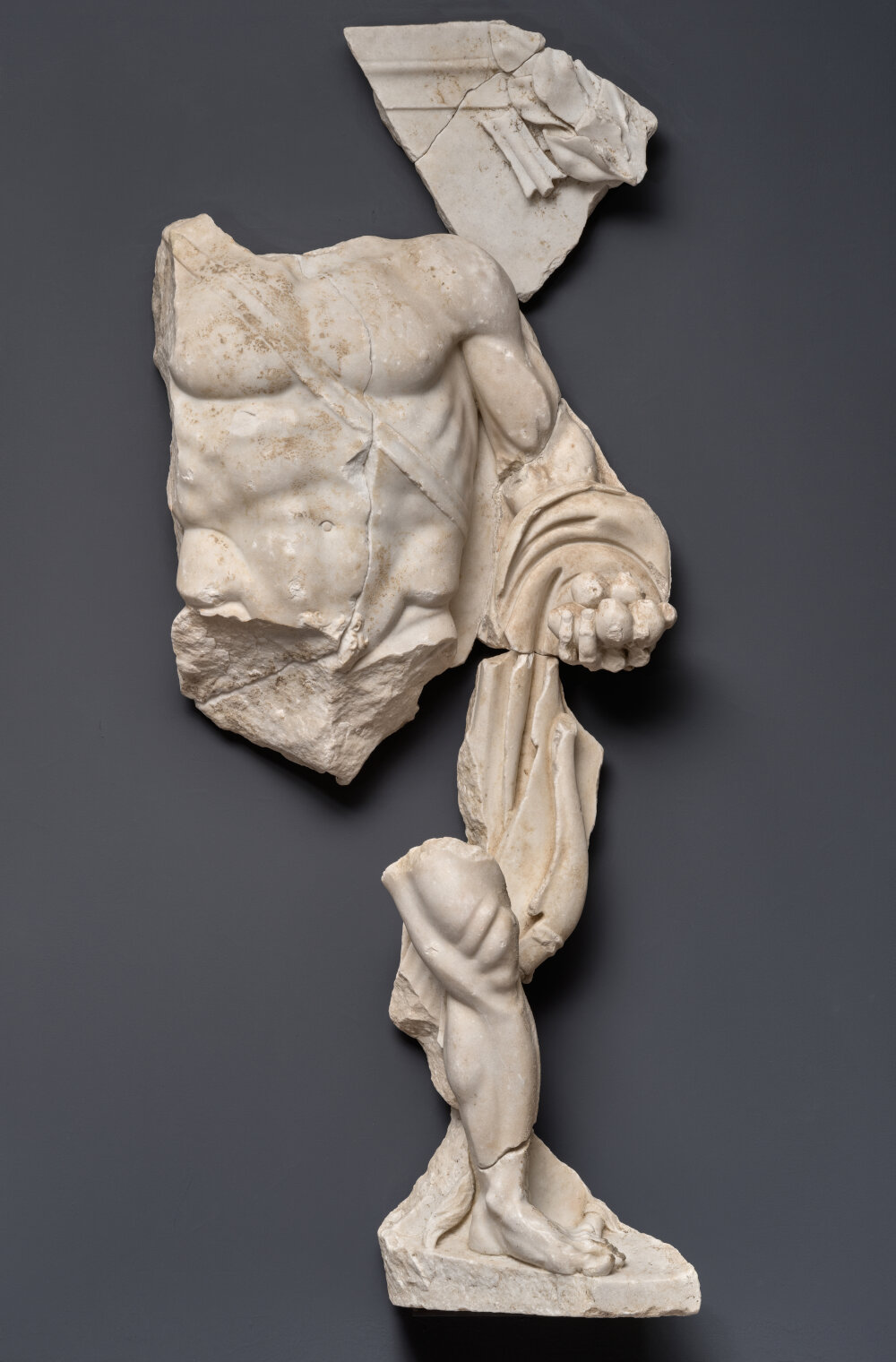

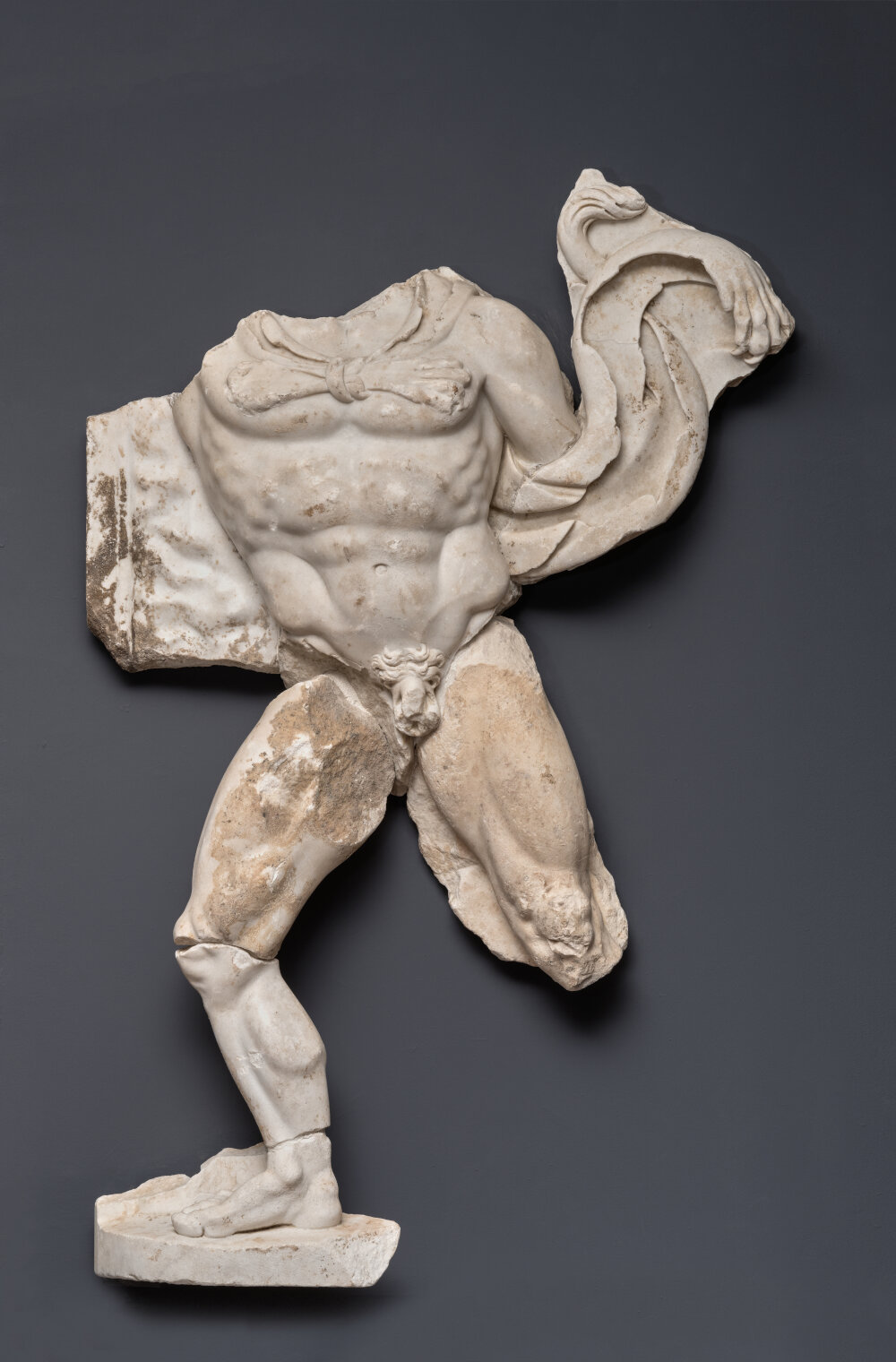

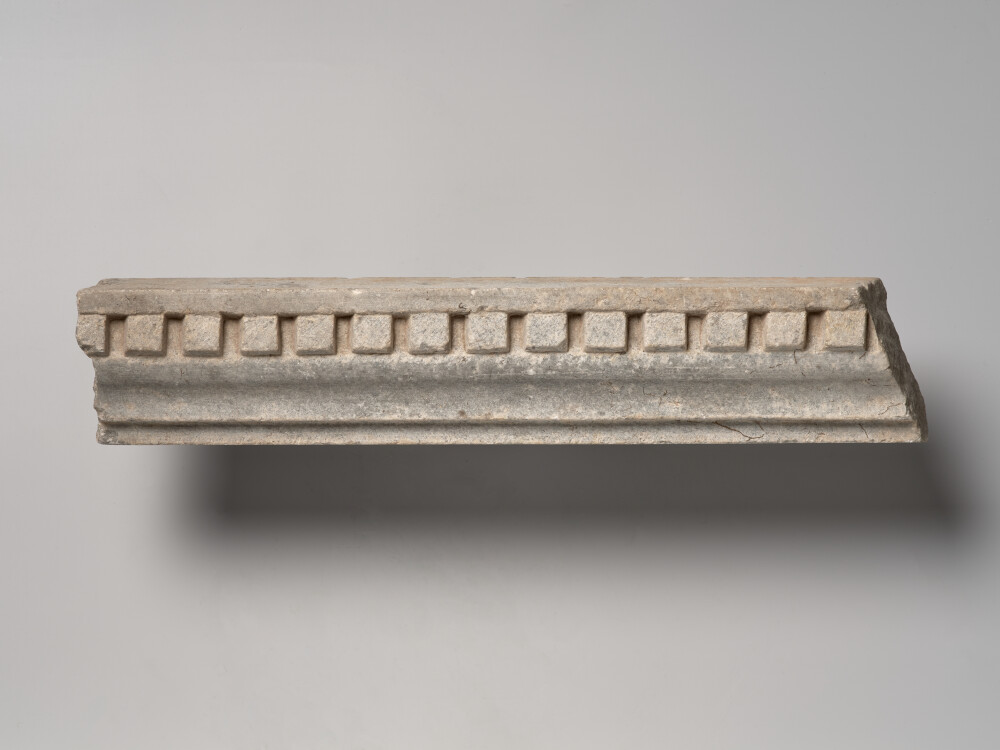

The archaeologist had indeed identified common stylistic traits between the cycle of the Labours of Hercules and the busts of the gods depicted on round shields (imagines clipeatae) L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris, 1901, pp. 91-92.. More recently, these connections have been confirmed and extended, and the group has even expanded considerably with the inclusion of the series of theatre masks, the series of Bacchic masks and seasons and the Assembly of Philosophers with Socrates M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, pp. 198-200 ; J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : Époque julio-claudienne, 1.1 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2005, pp. 126-137.. Should the representations of the headless Isis and Harpocrates be included? The connection between these last two in the round sculptures and the great high relief of Serapis raises further questions. The absence of a head for the statue of Isis, on the one hand, and the differences in the way Harpocrates’ hair is represented on the other, tend to preclude any suggestion of homogeneity regarding this isiac triad. Because of his hair, the formal characteristics of which can be compared to works dating from after the High Empire, Serapis, the great god of Alexandria, stands out on a slab, the double framing band of which is strongly reminiscent of the reliefs of Hercules and the Assembly of Philosophers. The intervention of the same workshop is therefore not to be ruled out.

An exceptional dynastic group and decor

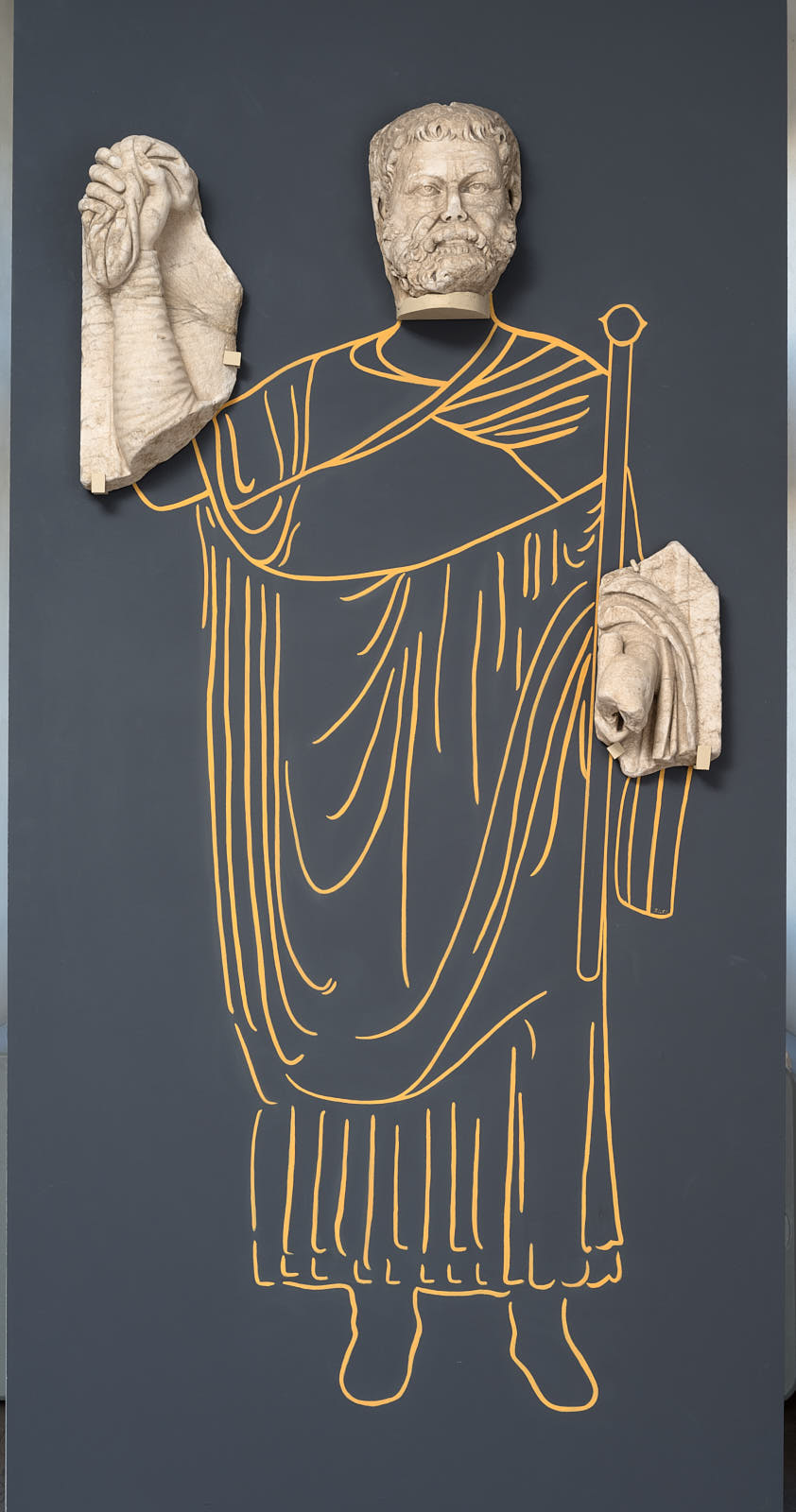

Several works with varying degrees of damage were attributed by J.-C. Balty to the Tetrarchy, and more specifically to the 290s. In this series, there are four complete heads and a fifth, very incomplete one. They are to be associated with certain elements of a recently restored relief depicting a standing man, wearing a long-sleeved tunic and a toga M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden, 1999, p. 32.; the right forearm of this solemn, front-facing effigy, with its hand holding the mappa (cloth), is not lost, contrary to what was sometimes written L.M. Stirling, The Learned Collector : Mythological Statuettes and Classical Taste in Late Antique Gaul, Ann Arbor, 2005, p. 61..

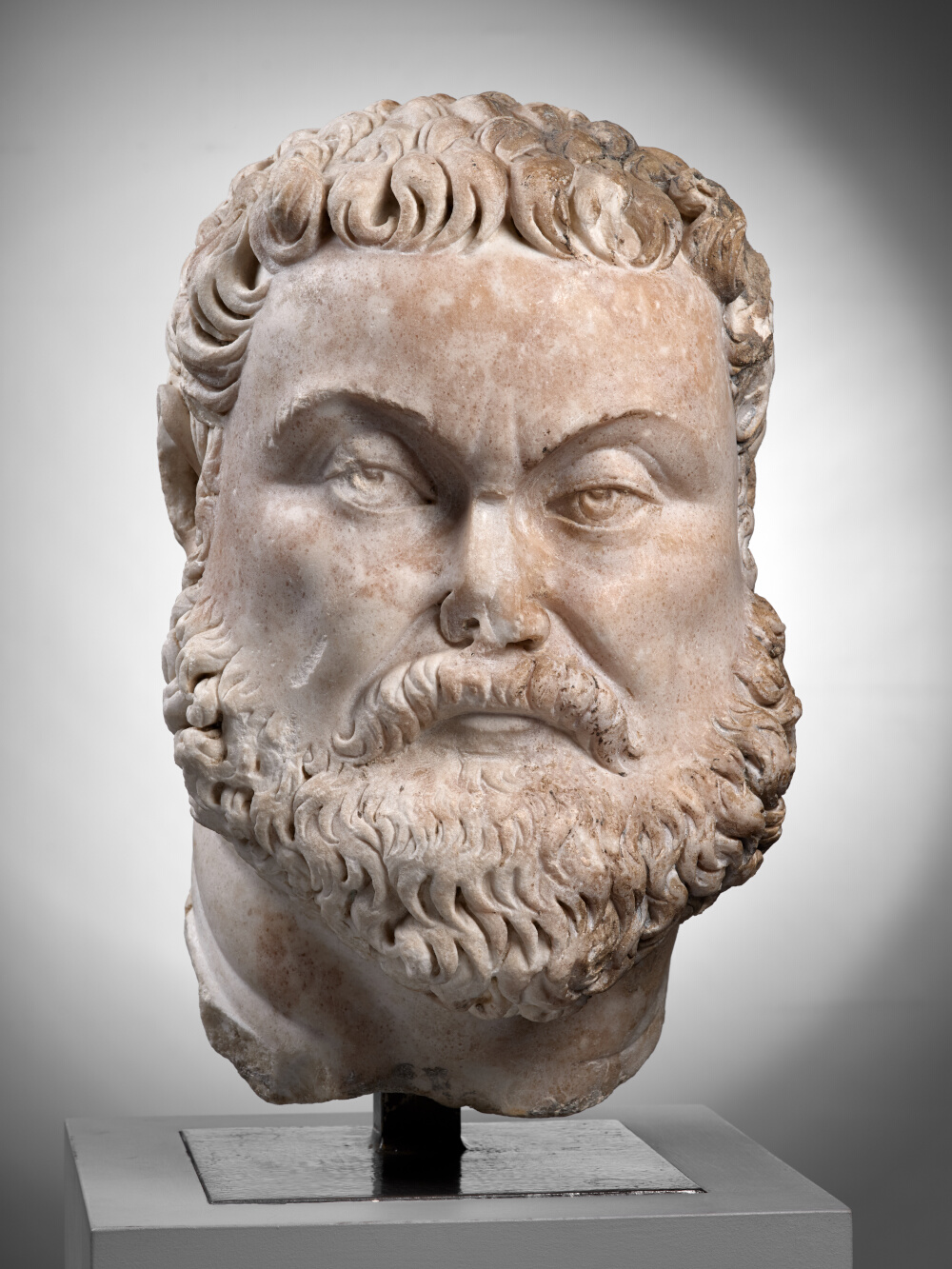

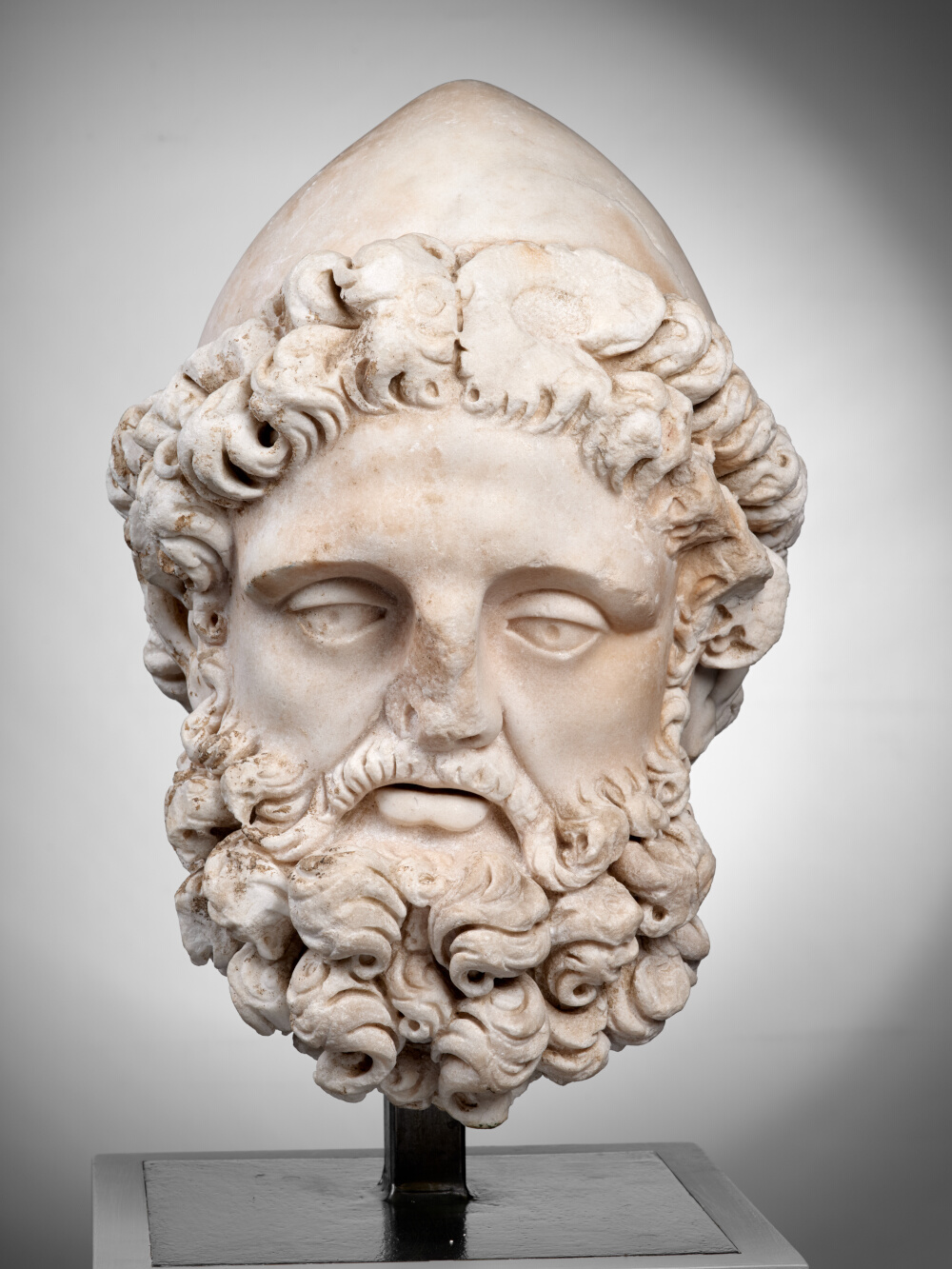

A rigorous and powerful demonstration allowed J.-C. Balty to identify in these very rare images of the Emperor Maximian Hercules, his wife, Eutropia, their son, Maxentius, and their daughter-in-law, Valeria Maximilla. Several common traits link these dynastic portraits with other sculptures whose themes of Hellenic ancestry are combined with formal characters that resonate with the art inherent to Late Antiquity. There are indeed notable similarities, as previously mentioned, between the heads of the Herculean cycle, the medallions of the gods, the Serapis, certain masks, and the relief that includes Socrates: the stylisation of physical features is associated, in these works, with thick curly hair and beards, the tapered ends of which form a series of locks divided into two or three strands, enhanced by deep circular drill holes M. Bergmann, « Un ensemble de sculptures de la villa romaine de Chiragan, oeuvre de sculpteurs d’Asie Mineure, en marbre de Saint-Béat ?, » J. Cabanot, R. Sablayrolles, J.-L. Schenck (eds.), Les marbres blancs des Pyrénées : approches scientifiques et historiques. Colloque, 14-16 octobre 1993, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, 1995, pp. 197–205, p. 198 ; D. Cazes et al., Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris, 1999, p. 85 ; J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : Époque julio-claudienne, 1.1 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2005, pp. 126-127..

The decor, presumably introduced from the 280s, the design of which may have extended to the turn of the century, is probably related to the creation and installation of the monumental portrait statues representing members of the family of Augustus Maximian M. Bergmann, « Un ensemble de sculptures de la villa romaine de Chiragan, oeuvre de sculpteurs d’Asie Mineure, en marbre de Saint-Béat ?, » J. Cabanot, R. Sablayrolles, J.-L. Schenck (eds.), Les marbres blancs des Pyrénées : approches scientifiques et historiques. Colloque, 14-16 octobre 1993, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, 1995, pp. 197–205, pp. 198-200 ; J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : La Tétrarchie, 1.5 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2008, pp. 126-129.. These years are those of the campaign conducted in 286 in Gaul by the Emperor against the Bagaudae. These peasant insurgents, « shepherds and brigands » according to Aurelius Victor, were « united by two chiefs, Elianus and Amandus, and had ravaged the countryside prior to invading the cities » (« …Helianum Amandum que per Galliam excita manu agrestium ac latronum, quos Bagaudas incolae vocant, populatis late agris plerasque urbium tentare… ») A. Victor, Liber de Caesaribus, 360 (circa), XXXIX, 17.. In his speech to the glory of Maximian, the rhetorician Mamertinus assimilates these rural peoples to giants that Jupiter had fought Mamertin, Panégyrique, 3rd century, X (2), 4, 2.. The campaign against the Bagaudae, an event that supposedly allowed Maximian to take the title of Augustus, may well have contributed to the genesis of the great cycle.

It is also known that, from Trier, Maximian later left to fight in Spain, in the spring of 296, to put an end to the violence perpetrated by the Franks who had been involved in numerous acts of piracy along the whole coast of the Iberian Peninsula since at least the beginning of the decade. This action allegedly earned him the epithet of « Iberian Ares » (Iberikos Arès). Africa was to be the next stage, at the end of the winter of 297P. Maymó i Capdevila, « Maximiano en campaña : matizaciones cronológicas a las campañas hispanas y africanas del Augusto Hercúleo, » 12, 2000, pp. 229–257, en partic. p. 230 ; J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : La Tétrarchie, 1.5 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2008, p. 130.. Beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, Maximian had to contend with the Moorish people of Quinquegentiani, a semi-nomadic tribe that had attacked the Roman territories. Defeated for the first time by Aurelius Litua, the governor of Caesarea during the winter of 292-293, they resumed their fighting, which led to a new campaign being launched by Maximian in 297 J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : La Tétrarchie, 1.5 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2008, p. 130..

The reliefs of Hercules are clear on this count: the son of Jupiter is a civilizing hero, a victor over barbarism and monsters. Was Maximian not also helping to save the universe under the aegis of the gods? This is emphasised in particular by the two eulogies delivered in his honour that evoke the invasions of the German barbarians, the usurpers, the looting perpetrated by rebellious peasants and, finally, the pirates. The  coins merely endorsed this mission. Emperor Maximian thus undoubtedly embodied a hero; he was the new Hercules. This effigy, which represents an impressively large bearded man with an imperious expression, most certainly originated in the same sculpture workshop as the reliefs of the medallions and the Labours of Hercules.

coins merely endorsed this mission. Emperor Maximian thus undoubtedly embodied a hero; he was the new Hercules. This effigy, which represents an impressively large bearded man with an imperious expression, most certainly originated in the same sculpture workshop as the reliefs of the medallions and the Labours of Hercules.

Archaeological sources and chronology

According to Léon Joulin’s census, 151 coins were unearthed at the Chiragan site. While 25 of these were impossible to decipher, 22 were attributed to the first century, and 23 to the following century. 23 other mints date back to the 3rd century and no less than 58 are believed to belong to the 4th century alone. Only 18 of these coins are still present in the medallion kept at the Musée Saint-Raymond V. Geneviève, « Les monnaies des établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane. 2 : Les monnaies des sites de Chiragan, Bordier, Sana, Coulieu, Saint-Cizy et du Tuc-de-Mourlan, » Mémoires de la Société archéologique du Midi de la France, LXVIII, 2008, pp. 95–140, en partic. pp. 98-100..

Among the discoveries made in the immediate surroundings was a lot unearthed at the Tuc-de-Mourlan site. Located three and a half kilometres to the east of the villa, on the edges of the present communes of Martres-Tolosane and Boussens, this site had been identified as a vicus by Léon Joulin. This modest lowland settlement was made up of mostly rectangular buildings, aligned on either side of the road that led from Tolosa to Aquae Tarbellicae (Dax) L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris, 1901, p. 179 ; P. Sillières, « Les campagnes, » J.-M. Pailler (ed.), Tolosa: nouvelles recherches sur Toulouse et son territoire dans l’Antiquité, Rome, 2002, pp. 373–402, p. 385.. The construction thus belonged to the series of numerous settlements recorded in this sector, mostly spread over the left bank of the Garonne, the area best suited to traffic and trade. Along both the road and the river, these constructions included villae (Chiragan, Bordier, Sana and Coulieu) as well as groups of agricultural and commercial buildings (Saint-Cizy, le Tuc-de-Mourlan) L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris, 1901, pp. 162-184..

The coins found on the Tuc-de-Mourlan site, just a stone’s throw from the buildings on the site of the famous villa, included a denarius that caught the attention of Vincent Geneviève.  This issue, recently examined by the expert eye of the numismatist, is credited to the workshop in Lyon, and is among the first to have been minted under the ‘rule of two’ formed by Diocletian and his co-emperor Maximian Hercules.

This issue, recently examined by the expert eye of the numismatist, is credited to the workshop in Lyon, and is among the first to have been minted under the ‘rule of two’ formed by Diocletian and his co-emperor Maximian Hercules.  The reverse side bearing the inscription IOVI CONSERVATORI (« to Jupiter the Protector ») was therefore a tribute formulated in the dative case in Latin that accompanies the image of the omnipotent protective god and defender of the emperor Diocletian, standing on the left with an eagle, a thunderbolt held in his lowered right hand, and a sceptre in the left. As explained by the researcher, in those days, denarii and quinarii were « exceptional coins, whose primary purpose was not to circulate but more specifically to mark and celebrate an event« V. Geneviève, « Un denier inédit de Dioclétien frappé à Lyon à la fin de l’année 286, découvert au XIXe siècle sur le site du Tuc-de-Mourlan (Martres-Tolosane, Haute-Garonne), » Cahiers Numismatiques, 180, 2009, pp. 31–39, en partic. p. _3_7.. The apparent modesty of this clue should not therefore overshadow its significance, as it can be seen as probable proof of the presence of a protagonist directly linked to imperial decisions and initiatives.

The reverse side bearing the inscription IOVI CONSERVATORI (« to Jupiter the Protector ») was therefore a tribute formulated in the dative case in Latin that accompanies the image of the omnipotent protective god and defender of the emperor Diocletian, standing on the left with an eagle, a thunderbolt held in his lowered right hand, and a sceptre in the left. As explained by the researcher, in those days, denarii and quinarii were « exceptional coins, whose primary purpose was not to circulate but more specifically to mark and celebrate an event« V. Geneviève, « Un denier inédit de Dioclétien frappé à Lyon à la fin de l’année 286, découvert au XIXe siècle sur le site du Tuc-de-Mourlan (Martres-Tolosane, Haute-Garonne), » Cahiers Numismatiques, 180, 2009, pp. 31–39, en partic. p. _3_7.. The apparent modesty of this clue should not therefore overshadow its significance, as it can be seen as probable proof of the presence of a protagonist directly linked to imperial decisions and initiatives.

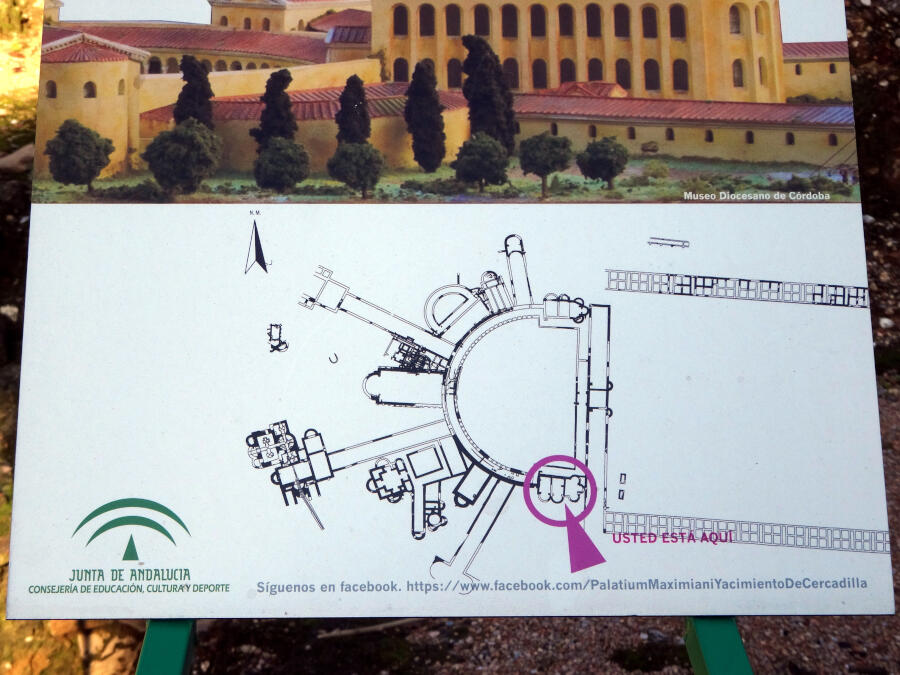

Further proof can be added to this numismatic record, but to do so we must leave Chiragan and its surroundings. For it is in Spain and Portugal that several archaeological sources, in the realm of epigraphs, sculptures and architecture can undeniably help us to better understand the transformations and dynamism of the villa on the banks of the river Garonne during the Tetrarchy. This evidence was in fact placed in a historical context similar to that of Diocletian’s denarius, but in this case it is milestones, which prove that the roads in the Iberian Peninsula were restored in the first half of the 290s, as well as a triumphal bas-relief of Augusto Emerita (the present-day Mérida), and the  bas-relief triomphal de Mérida (Augusto Emerita) ou encore du

bas-relief triomphal de Mérida (Augusto Emerita) ou encore du  Roman Palacio de Cercadilla in Cordoba, also dating back to the first Tetrarchy, the construction of which is attributed to the Emperor himself, and is said to have been completed very swiftly Z. Mráv, « Maniakion – The Golden Torc in Late Roman and Early Byzantine Army. Preliminary Research Report, » T. Vida (ed.), Romana Gothica II, The Frontier World, Romans, Barbarians and Military Culture, Budapest 1-2 Octobre 2010, Budapest, 2015, pp. 287–303, p. 289, 290, fig. 4 ; J. Arce Martínez, « Un relieve triunfal de Maximiano Herculeo en Mérida y el P. Stras. 480, » Cuadernos emeritenses, 22, 2003, pp. 47–70, en partic. 47-70 ; R. Hidalgo Prieto, Espacio público y espacio privado en el conjunto palatino de Cercadilla (Córdoba) : el aula central y las termas (Arqueología. Serie Monografías. Cercadilla), Seville, 1996, pp. 149-156 ; J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : La Tétrarchie, 1.5 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2008, pp. p. 130-131, n. 51, fig. 110.. All of these are believed to be dependent on the military work of Maximian Hercules.

Roman Palacio de Cercadilla in Cordoba, also dating back to the first Tetrarchy, the construction of which is attributed to the Emperor himself, and is said to have been completed very swiftly Z. Mráv, « Maniakion – The Golden Torc in Late Roman and Early Byzantine Army. Preliminary Research Report, » T. Vida (ed.), Romana Gothica II, The Frontier World, Romans, Barbarians and Military Culture, Budapest 1-2 Octobre 2010, Budapest, 2015, pp. 287–303, p. 289, 290, fig. 4 ; J. Arce Martínez, « Un relieve triunfal de Maximiano Herculeo en Mérida y el P. Stras. 480, » Cuadernos emeritenses, 22, 2003, pp. 47–70, en partic. 47-70 ; R. Hidalgo Prieto, Espacio público y espacio privado en el conjunto palatino de Cercadilla (Córdoba) : el aula central y las termas (Arqueología. Serie Monografías. Cercadilla), Seville, 1996, pp. 149-156 ; J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : La Tétrarchie, 1.5 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2008, pp. p. 130-131, n. 51, fig. 110.. All of these are believed to be dependent on the military work of Maximian Hercules.

Chiragan gave us two portraits of this emperor, a colossal head, probably the remains of a standing statue according to J.-C. Balty, and the exceptional albeit incomplete bas-relief, mentioned earlier. The distinctive appearance of this effigy is explained when compared to two famous in the round sculptures kept at the Musée du Capitole and exhibited at the Centrale Montemartini. These full-length portraits, known as « the magistrates », created at the end of the 4th century, were discovered in Rome in the Gardens of Liciniani (Horti Liciniani) M. Cima, « Statua di Magistrato anziano, » S. Ensoli, E. La Rocca (eds.), Aurea Roma : dalla città pagana alla città cristiana. Mostra, Palazzo delle esposizioni, Roma, 22 dicembre 2000-20 aprile 2001, Rome, 2000, p. 432-433, no 12.. Their clothing is certainly identical to those worn by Maximian Hercules in Chiragan. Over the long-sleeved tunic, a toga has a contabulatio, a wide oblique fold across the chest that forms a layer of flat, compressed pleats; a draping technique known since the reign of Severus. The mappa is another feature that links, iconographically-speaking, the Roman magistrates from the incomplete bas-relief found on the banks of the Garonne. This white cloth, which was thrown into the arena to mark the start of chariot races, alluded to the inauguration of the games within the scope of a Consulate. A magisterial position Maximian occupied eight times, between 287 and 304.

Pascal Capus

To cite this section

Capus P., « Late antiquity », in The sculptures of the roman villa of Chiragan, Toulouse, 2019, online <https://villachiragan.saintraymond.toulouse.fr/partie-04>.