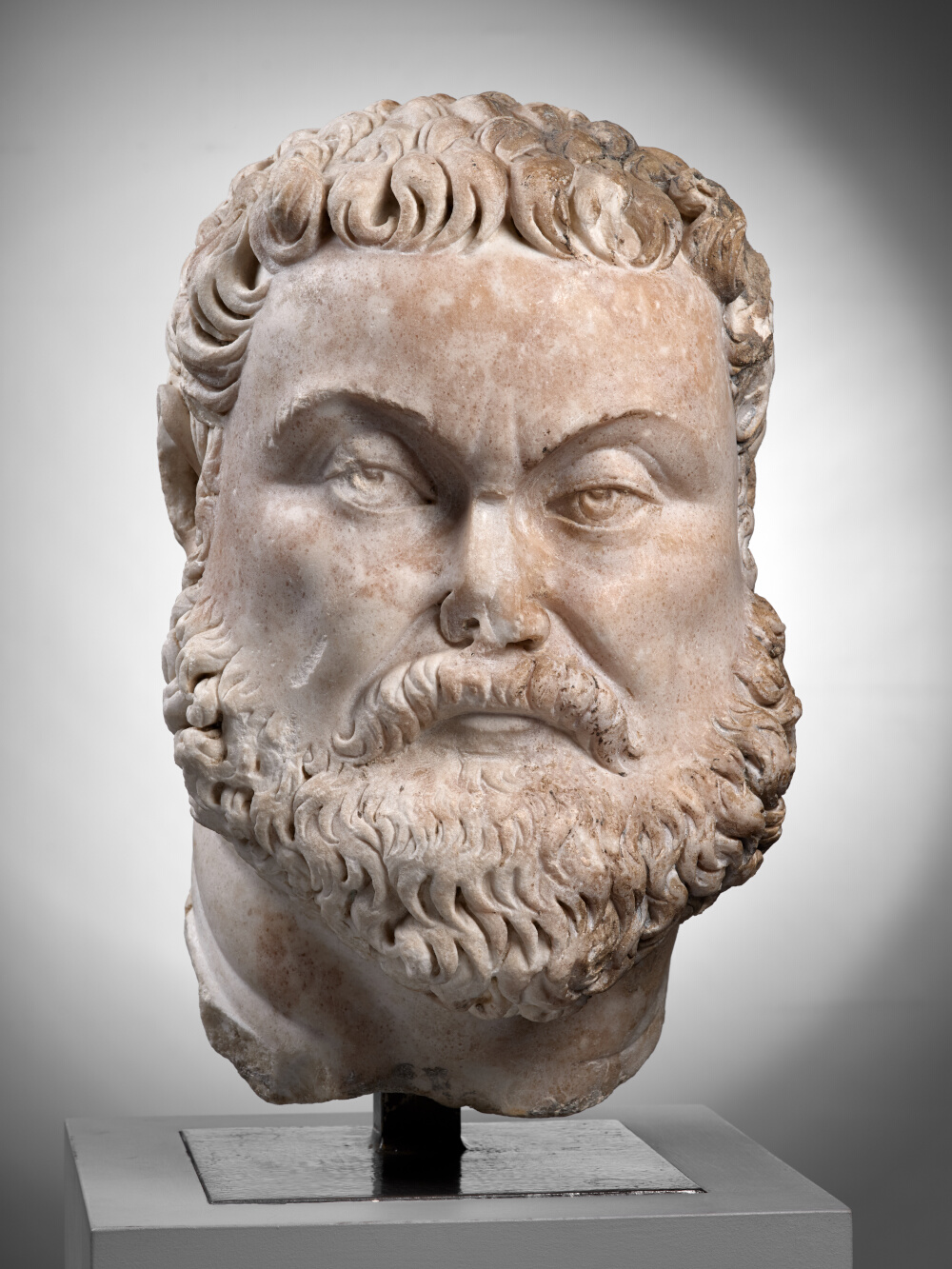

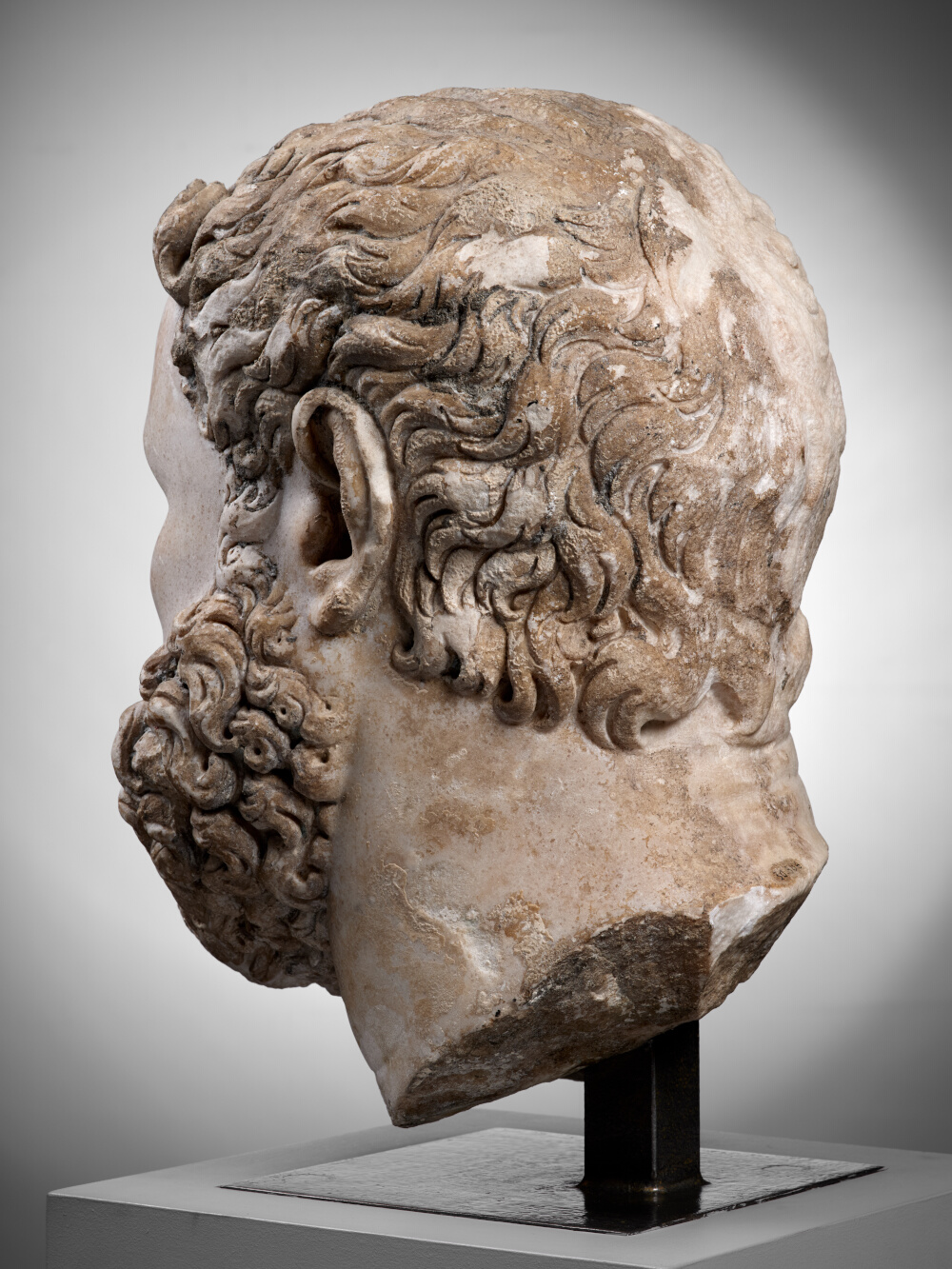

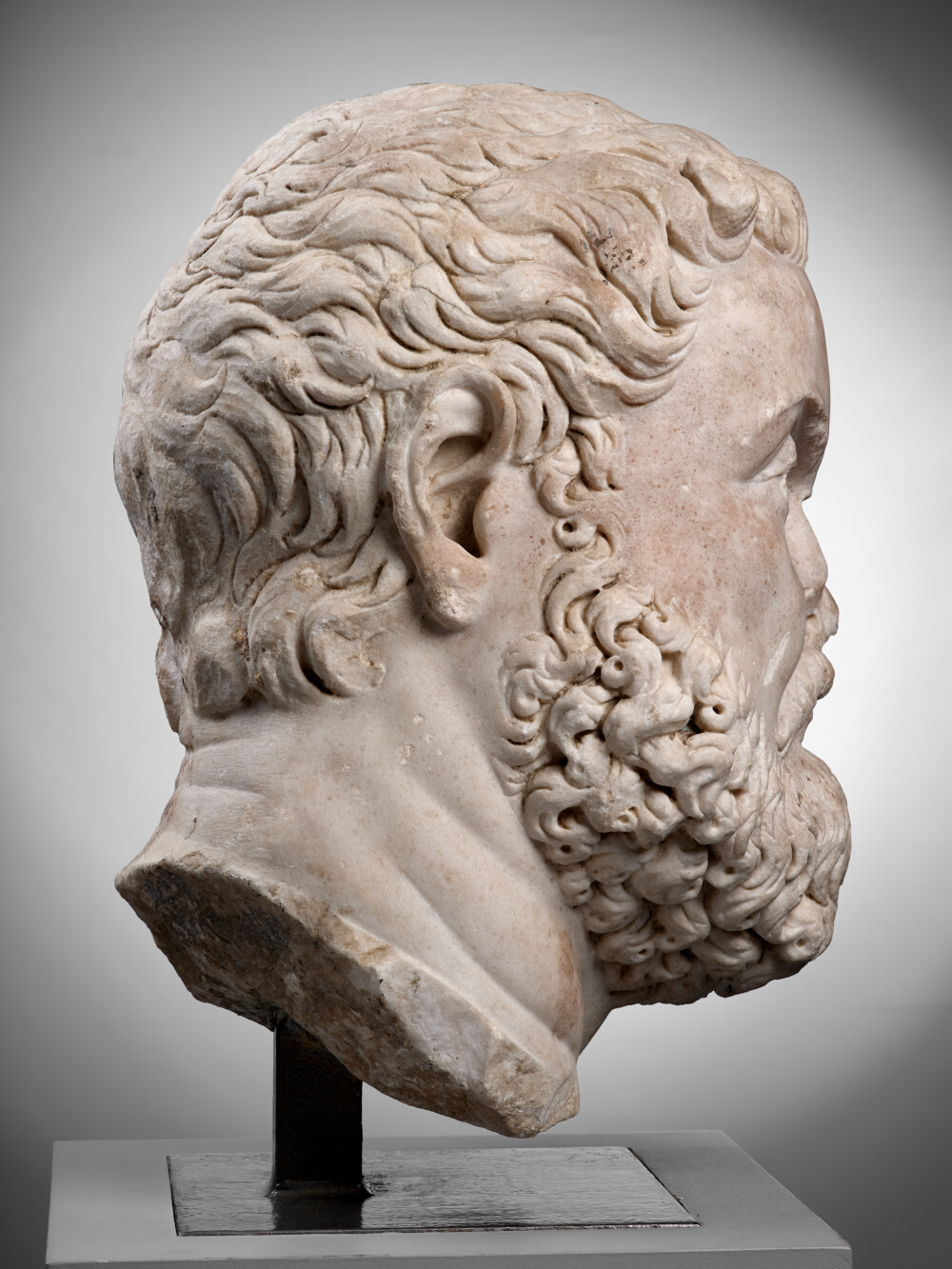

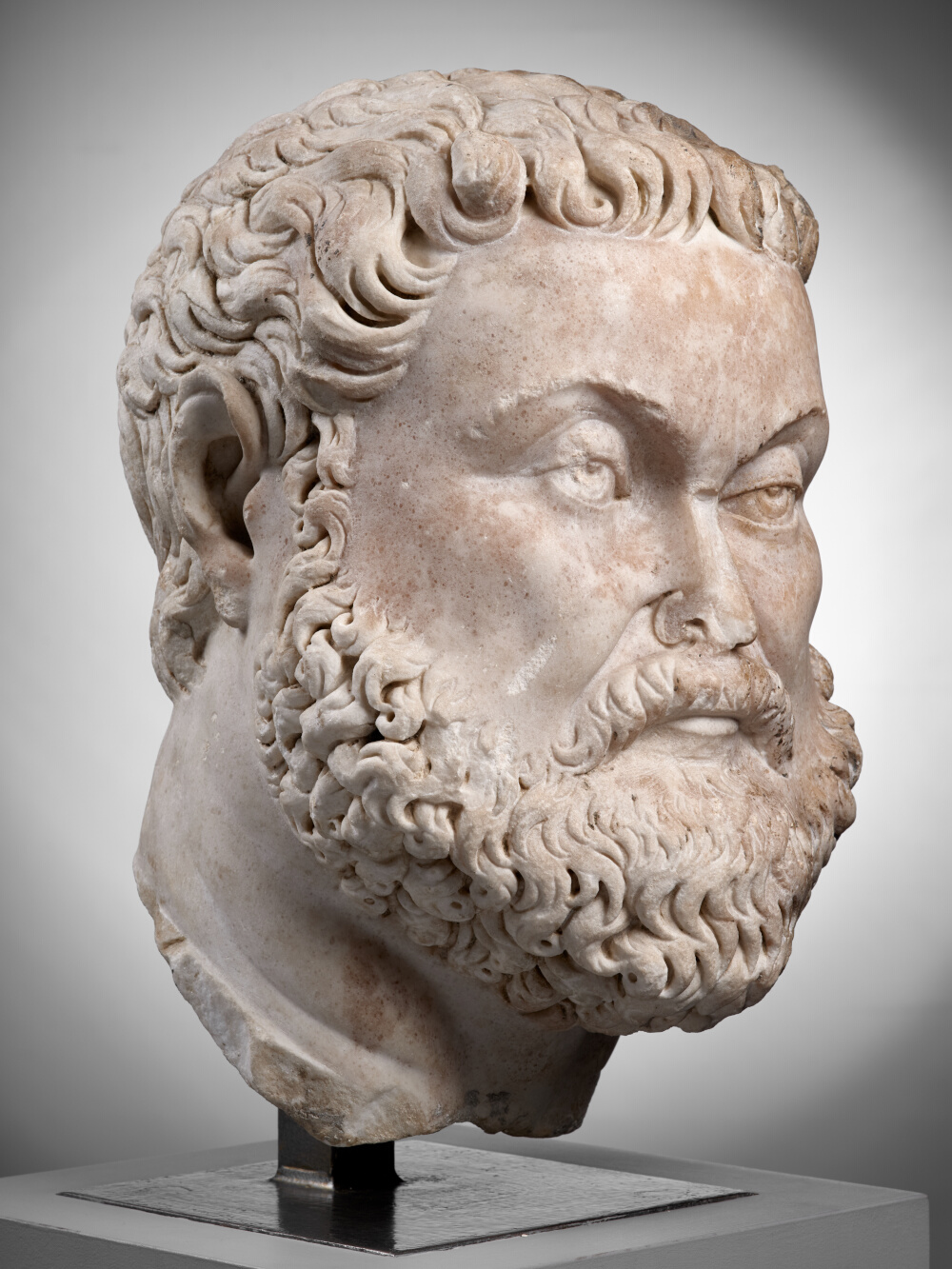

Head of quasi-colossus of Maximian Herculius

- Biographic data

- Around 240/250-310, Emperor from 286 to 305 and from 306 to 310

- Date de création

- After 293

- Material

- Saint-Béat marble (Haute-Garonne)

- Dimensions

- H. 43 x l. 26 x P. 30,5 (cm)

- Inventory number

- Ra 34 b

- Photo credits

- Daniel Martin

Diocletian was proclaimed emperor (Augustus) at the end of the year 284. Faced with the threats of foreign peoples on the limes (border) as well as the attempts made by certain generals to usurp his power, the sovereign appointed a co-emperor, Maximian, who was granted the title of Caesar. Both rulers were from Central Europe: Maximian, born in Pannonia between five and eight years before Diocletian, was originally from Dalmatia.

In 286, Diocletian raised Maximian to the rank of Augustus, a title that made him an emperor in his own right. This diarchy, or corule, which resembled that of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus in the previous century, was however destined to evolve. Thus, on the 1st March 293, a new development in the history of imperial institutions was introduced in the form of a much more innovative form of government: the Tetrarchy. The two Augusti, Diocletian and Maximian, joined forces with two Caesars. Maximian, appointed Augustus of the West, was assisted by Constantius Chlorus, while Diocletian, appointed Augustus of the East, was assisted by Galerius. Maximian chose as his protector Hercules, a hero who had become immortal, and administered Italy, Raetia (a province between the Danube and the Veneto), Africa and Spain. His Caesar, Constantius Chlorus, father of the future Constantine the Great, devoted himself to the provinces of Gaul and Brittany (now Wales and England).

As explained in the introduction to this section, all the decorative elements made from marble sourced in Saint-Béat, as well as these four portraits probably belong to the period of this first Tetrarchy and seem to testify to the lavish restoration of Villa Chiragan under Maximian. The statue to which this head belonged must have stood 2.75 metres tall, meaning it was therefore larger than the second, very fragmentary representation of this same emperor, which forms a particularly impressive relief, the missing parts of which are now graphically reproduced in the museum.

The Emperor, who was not content to consider the now immortal Hercules as his personal tutelary god, chose to legitimise his power by insisting that he was actually the god’s direct descendant. He made him the patron saint of his family, which in turn became Herculean A. Eppinger, Hercules in der Spätantike : die Rolle des Heros im Spannungsfeld von Heidentum und Christentum (Philippika), Wiesbaden, 2015, p. 158.. Finally, it is worth noting that in this portrait, the outline of the hair of the fringe, temples and beard, are unmistakably similar to those of the head of Hercules fighting Diomedes in the great sculptural cycle, and it is quite likely that both were displayed relatively close to each other.

According to J.-C. Balty, Les portraits romains, La Tétrarchie, 1.5 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, 2008, p. 33-53.

Bibliography

- Ensoli, La Rocca 2000 S. Ensoli, E. La Rocca (eds.), Aurea Roma : dalla città pagana alla città cristiana. Mostra, Palazzo delle esposizioni, Roma, 22 dicembre 2000-20 aprile 2001, Rome. p. 459-460, no 59

- Balmelle 2001 C. Balmelle, Les demeures aristocratiques d’Aquitaine : société et culture de l’Antiquité tardive dans le Sud-Ouest de la Gaule (Mémoires 5 – Aquitania, suppl. 10), Bordeaux-Paris. p. 230, fig. 125 a

- Balty, Cazes 2008 J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : La Tétrarchie, 1.5 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse. ill. de couv., p. 13, 15, 24-25, 35, 37 fig. 5, 41 fig. 8, 45 fig. 14, 48, 50-51, 53 fig. 23, 127 fig 104, 128 fig. 106, 129 fig. 108

- Beckmann 2020 S.E. Beckmann, « The Idiom of Urban Display: Architectural Relief Sculpture in the Late Roman Villa of Chiragan (Haute-Garonne), » American Journal of Archaeology, 124, 1, pp. 133–160. p. 146-148, fig. 12

- Bergmann 1999 M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden. p. 26-44, pl. 9-3, 11-5, 12, 13-4

- Bergmann 1995 M. Bergmann, « Un ensemble de sculptures de la villa romaine de Chiragan, oeuvre de sculpteurs d’Asie Mineure, en marbre de Saint-Béat ?, » J. Cabanot, R. Sablayrolles, J.-L. Schenck (eds.), Les marbres blancs des Pyrénées : approches scientifiques et historiques. Colloque, 14-16 octobre 1993, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, pp. 197–205. p. 198, fig. 2-3, p. 200

- Cazes et al. 1999 D. Cazes, E. Ugaglia, V. Geneviève, L. Mouysset, J.-C. Arramond, Q. Cazes, Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris. p. 143

- Du Mège 1835 A. Du Mège, Description du musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 129-130, no 230

- Eppinger 2015 A. Eppinger, Hercules in der Spätantike : die Rolle des Heros im Spannungsfeld von Heidentum und Christentum (Philippika), Wiesbaden. p. 158

- Espérandieu 1908 É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, 2. Aquitaine, Paris. p. 32, no 892.8

- Joulin 1901 L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris. p. 304, pl. VI, no 60

- Massendari 2006 J. Massendari, La Haute-Garonne : hormis le Comminges et Toulouse 31/1 (Carte archéologique de la Gaule), Paris. p. 248, fig. 112

- Rachou 1912 H. Rachou, Catalogue des collections de sculpture et d’épigraphie du musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 32-33, no 34 b

- Roschach 1865 E. Roschach, Catalogue des antiquités et des objets d’art, Toulouse. p. 30, no 50

- Rosso 2006 E. Rosso, L’image de l’empereur en Gaule romaine : portraits et inscriptions (Archéologie et histoire de l’art), Paris. p. 486-488, no 236

- Turcan 2006 R. Turcan, Constantin en son temps : le Baptême ou la Pourpre ?, Dijon. p. 32, fig. 9

- Musée Saint-Raymond 2011 Musée Saint-Raymond, L’essentiel des collections (Les guides du MSR), Toulouse. p. 30-31

- Musée Saint-Raymond 1995 Musée Saint-Raymond, Le regard de Rome : portraits romains des musées de Mérida, Toulouse et Tarragona. Exhibition, Mérida, Museo nacional de arte romano ; Toulouse, Musée Saint-Raymond ; Tarragone, Museu nacional arqueològic de Tarragona, 1995, Toulouse. p. 235, no 171

To cite this notice

Capus P., "Head of quasi-colossus of Maximian Herculius", in The sculptures of the roman villa of Chiragan, Toulouse, 2019, online <https://villachiragan.saintraymond.toulouse.fr/en/ark:/87276/a_ra_34_b>.