Assembly of philosophers (?)

- Type

- End of the 3rd-4th century

- Material

- Marble

- Dimensions

- H. 70 (Ra 116) 26 (Ra 95) x l. 30 (Ra 116) 35 (Ra 95) x P. 17.5 (Ra 116) 14 (Ra 95) (cm)

- Inventory number

- Ra 116-Ra 95

- Photo credits

- Daniel Martin

Two fragments, reunited at the end of the 19th century, make up what remains of a large and badly damaged marble tablet. The lower part, discovered during Albert Lebègue’s investigations in 1890-1891, shows a man in the foreground sitting at the foot of a herma, the upper part of which was unearthed as early as 1828-1830, during the excavations conducted by Alexandre Du Mège.

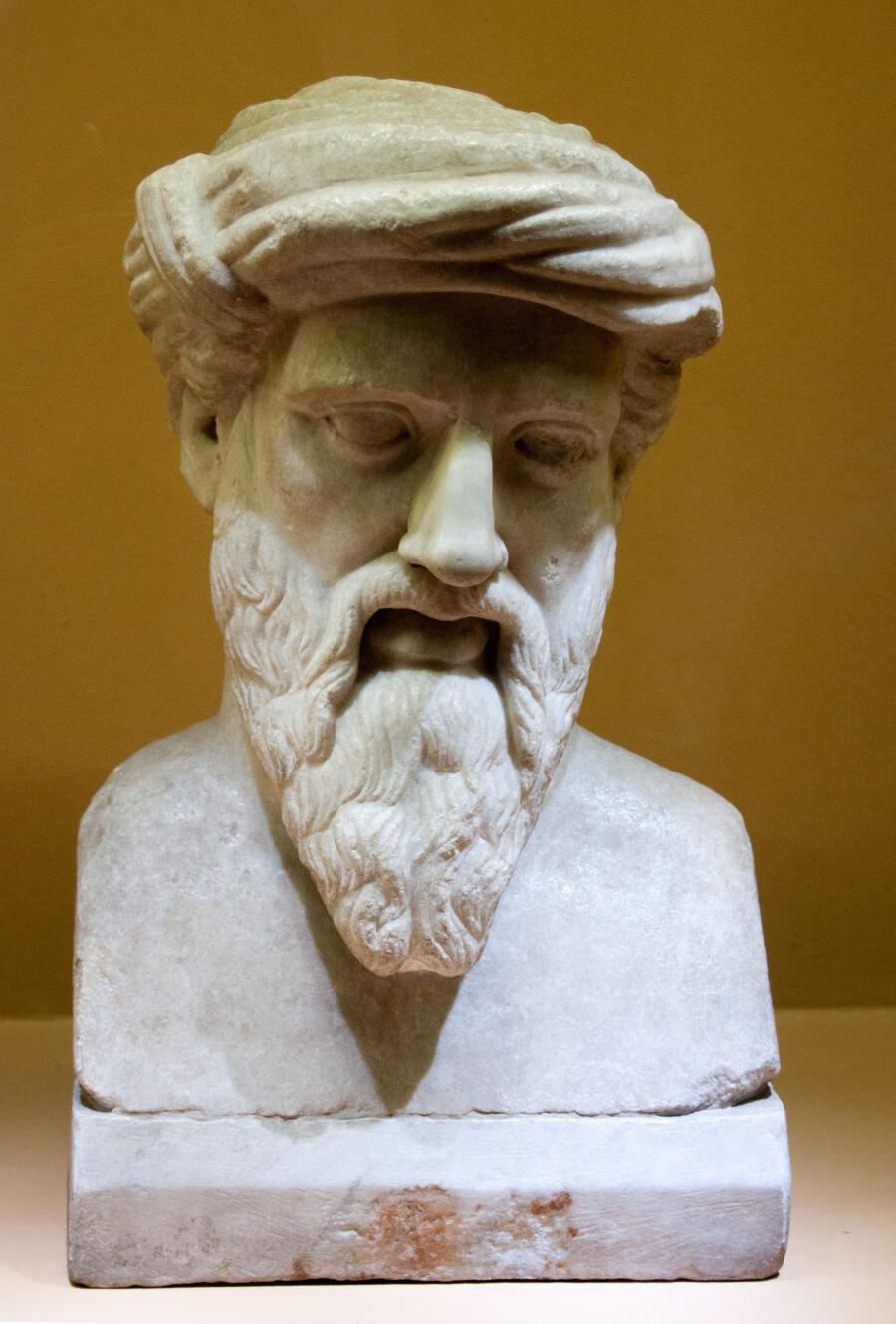

A herma is a composite sculpture that probably originated in Athens in the 6th century BC. Often inscribed with moralizing maxims, these so-called hermaic pillars could be used as gravestones, boundary stones and crossroad markers, as well as milestones to indicated distances from the heart of a city. This type of herma was hugely popular throughout the Roman world. Like the one depicted in the Chiragan relief, it boasted a sculpted, bearded head made of marble or bronze inserted into a quadrangular plinth. Here the head is facing right, but although the sculptor has favoured this more conventional profile view of the head, you only have to stand to the right of the tablet to see practically all of the protruding face, that is the whole nose, the beginning of the left brow ridge, the almost complete mouth, and the separate stands of fringe above the forehead. A wide ribbon encircles the skull horizontally and covers the top part of the forehead. It is kept in place by a thinner band that encircles the skull from the nape of the neck to the top of the head. The long, full beard consists of superimposed coils, separated by a deep horizontal furrow forming two vertical rows divided by a drill hole. The curls are made with the same tool, all of which curl around deep circular holes drilled at the ends of the strands of hair around the temples and at the back of the neck. When associated with the design of the sections of fringe, each ending in two or three strands, this working of the beard and the hairstyle are tantamount to a workshop signature, both on the reliefs depicting the Labours of Hercules and on the medallions of the gods.

Although Léon Joulin believed the noble head of this herma to be that of « Jupiter facing characters that have since been lost » L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris, 1901, p. 105., A. Hermary, taking as proof the headband that encircles the skull of this male representation, suggested that it could be Pythagoras A. Hermary, « Socrate à Toulouse, » Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise, 29, 1, 1996, pp. 21–30, en partic. pp. 29-30.. The a href= »/images/comp-ra-116-95-1.jpg » class= »comparaison »> herma head displayed in the Capitoline Museums</a>, now canonical and conventionally identified as being a portrait of the philosopher, could bear some similarities with our work, both in terms of the type of plinth and the long, tapered beard. Yet in this instance, the headband looks more like a turban, and the hair is nothing like the sophisticated long curls cascading onto the shoulders that are characteristic of the plinthed figure discovered in Chiragan. On this last point,

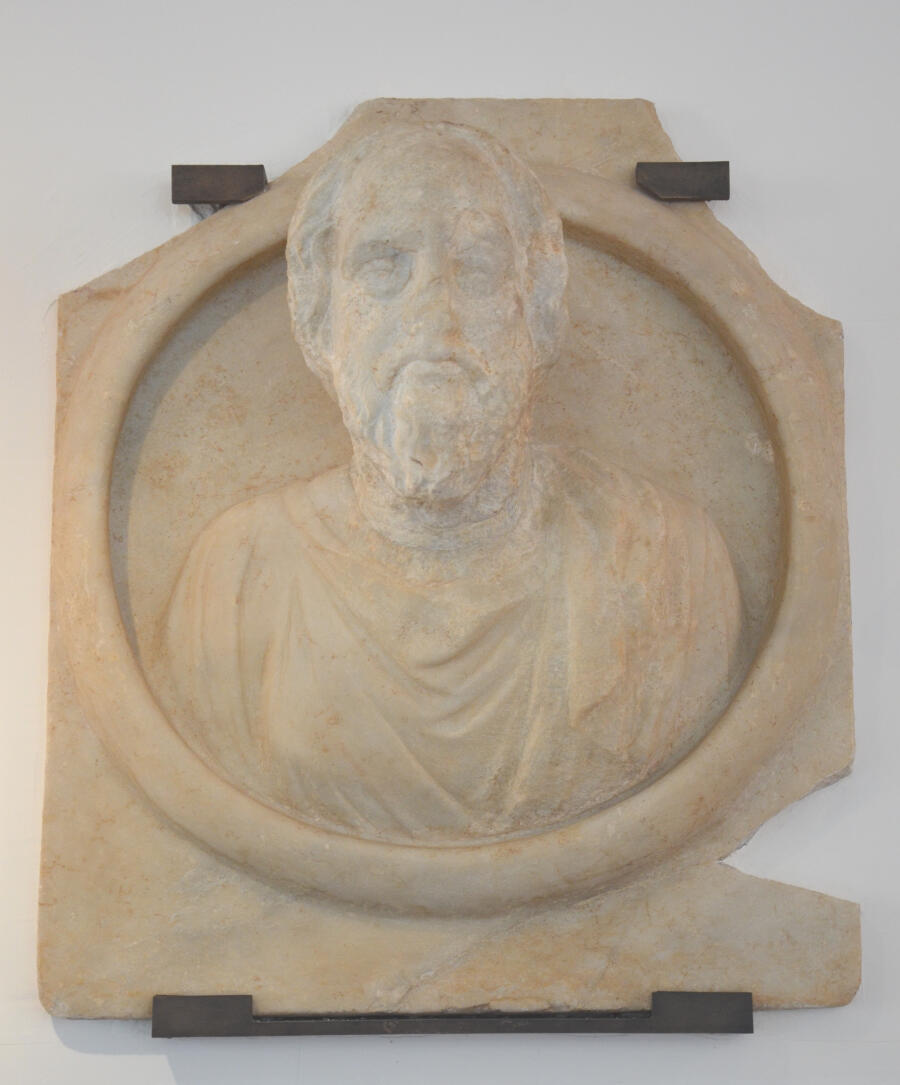

herma head displayed in the Capitoline Museums</a>, now canonical and conventionally identified as being a portrait of the philosopher, could bear some similarities with our work, both in terms of the type of plinth and the long, tapered beard. Yet in this instance, the headband looks more like a turban, and the hair is nothing like the sophisticated long curls cascading onto the shoulders that are characteristic of the plinthed figure discovered in Chiragan. On this last point,  another portrait, although not fully compliant with the relief in Toulouse, could perhaps be more akin to it. This copy is part of a series of busts on shields (imagines clipeatae), images of immortal gods discovered in Aphrodisias (Caria, Asia Minor) crafted between the end of the 4th century and the middle of the next. The marble scenography of the building, depicted as a philosophical school R.R.R. Smith, « Late Roman Philosopher Portraits from Aphrodisias, » The Journal of Roman Studies, 80, 1990, pp. 127–155, en partic. p. 127-128 et 130., is a reference to the greatest schools of thought through their main representatives. It therefore includes the head of Pythagoras, mentioned here for the sake of comparison. Discovered in 1968 among the rubble that filled the theatre, it was reunited much later with its original bust on a shield (clipeus) discovered in a completely different context in 1981, and engraved with the name of this illustrious intellectual R.R.R. Smith, « A New Portrait of Pythagoras, » K.T. Erim, International Aphrodisias colloquium (eds.), Aphrodisias Papers. 2, The Theatre, a Sculptor’s Workshop, Philosophers and Coin Types, Ann Arbor, 1991, pp. 159–167, figs. 1–6, p. 142, Pl. XI, 6p.. Because of the very symmetrical composition of the locks of hair and beard, the portrait of Aphrodisias, with its impersonal features, which have not been influenced by any known portrait of Pythagoras, and the flat and schematic folds of the himation (mantle) is similar in spirit to the medallions of the gods of Chiragan. The headband, although simpler, seems more in keeping with that of the sculpture found on the site located in Haut-Garonne, and bears no relation whatsoever to the imposing cloth of the turban on the head of the herma on display at the Capitoline Museums, which has since been adopted as the canonical portrait of the mathematician.

another portrait, although not fully compliant with the relief in Toulouse, could perhaps be more akin to it. This copy is part of a series of busts on shields (imagines clipeatae), images of immortal gods discovered in Aphrodisias (Caria, Asia Minor) crafted between the end of the 4th century and the middle of the next. The marble scenography of the building, depicted as a philosophical school R.R.R. Smith, « Late Roman Philosopher Portraits from Aphrodisias, » The Journal of Roman Studies, 80, 1990, pp. 127–155, en partic. p. 127-128 et 130., is a reference to the greatest schools of thought through their main representatives. It therefore includes the head of Pythagoras, mentioned here for the sake of comparison. Discovered in 1968 among the rubble that filled the theatre, it was reunited much later with its original bust on a shield (clipeus) discovered in a completely different context in 1981, and engraved with the name of this illustrious intellectual R.R.R. Smith, « A New Portrait of Pythagoras, » K.T. Erim, International Aphrodisias colloquium (eds.), Aphrodisias Papers. 2, The Theatre, a Sculptor’s Workshop, Philosophers and Coin Types, Ann Arbor, 1991, pp. 159–167, figs. 1–6, p. 142, Pl. XI, 6p.. Because of the very symmetrical composition of the locks of hair and beard, the portrait of Aphrodisias, with its impersonal features, which have not been influenced by any known portrait of Pythagoras, and the flat and schematic folds of the himation (mantle) is similar in spirit to the medallions of the gods of Chiragan. The headband, although simpler, seems more in keeping with that of the sculpture found on the site located in Haut-Garonne, and bears no relation whatsoever to the imposing cloth of the turban on the head of the herma on display at the Capitoline Museums, which has since been adopted as the canonical portrait of the mathematician.

In front of the hermaic pillar, Plato’s master Socrates is easily identified thanks to his pug-nosed features, his small and very deep-set eyes under prominent brow ridges, and his baldness. Plato Platon, Le Banquet, 380BC (circa), 215b-d, 216d, 221d-222a. and Xenophon Platon, Le Banquet, 380BC (circa), V, 7. had each in turn compared the features of the philosopher to those of a silenus. In his amorous speech, Alcibiades insists on this peculiarity, saying that Socrates « very much resembles the sileni found in sculptors’ workshops, portrayed by them alongside a syrinx and a flute… I also maintain that he resembles the satyr Marsyas, » to which he hastily added « the only difference between Marsyas and you, Socrates, is that you produce the same effect on us using only words, not instruments ». In sculpture, this physiognomy, which is so very characteristic, was used to render the face of the Athenian thinker based on a model that was very popular in Rome when seeking to represent him, that is the « B-type » model, designed towards the end of the 4th century BC, which clearly tempers the caricatured silenic features K. Lapatin, « Picturing Socrates, » S. Ahbel-Rappe, R. Kamtekar (eds.), A Companion to Socrates, Malden-Victoria,-Oxford, 2006, pp. 112–113, pp. 112-113.. On the relief found in Chiragan, the mantle, simply draped over the shoulders, reveals sagging pectorals. The « deliverer of souls » is seated, and his expression and the fact that his head is resting on his left hand, which has since disappeared, suggest a melancholic and meditative state of mind.

A fragment of relief, showing a now damaged bearded man’s head, is believed to be akin to the marble tablets featuring Socrates. The subject stretches beyond the surface area of the relief, and encroaches on the moulded frame that seems to extend the scene depicting the philosophers D. Cazes et al., Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris, 1999, p. 117.. The « Pythagorean » herma overflowed in a similar manner, as does the entire Herculean cycle, in which the figures are drawn out beyond the frames. This is indeed a feature which, without being unique in the context of ancient relief sculpture, nevertheless distinguishes, in Chiragan, the compositions of this particular workshop, commissioned to contribute to the lavish decor of the villa during Late Antiquity.

Representations of philosophers were frequently found in villas. Socrates, the founding father of philosophy, like Aristotle, were displayed in the private or semi-public setting of Roman residences at least from the beginning of the Empire P. Zanker, Die Maske des Sokrates : Das Bild des Intellektuellen in der antiken Kunst, Munich, 1995, p. 44, fig. 23 ; G. Sauron, Les décors privés des Romains : dans l’intimité des maîtres du monde, Paris, 2009, p. 272, fig. 229 et p. 275.. The fact that they were still part of displays during Late Antiquity should come as no surprise, despite the scarcity of unearthed specimens. As mentioned above with regard to Pythagoras, several figures on shields found at Aphrodisias, in a building that seems to have been a teaching place for the elite, represented great thinkers of Classical and also Late Antiquity R.R.R. Smith, « Late Roman Philosopher Portraits from Aphrodisias, » The Journal of Roman Studies, 80, 1990, pp. 127–155, en partic. pp. 127-155.. Portraits of philosophers were also presented in the form of hermae, in gardens or peristyles, centuries later, as evidenced by the relief discovered on the Chiragan estate. Hermae portraits maintained a link with the travelling messenger god Hermes, son of Zeus and Maia, after whom they were named, because of his function as a herald (Hermes Logios) S. Dillon, Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture : Contexts, Subjetcs and Styles, Cambridge, 2006, p. 31.. Another residence,  Villa Welschbillig (Rhineland-Palatinate), is yet another example of the importance given to the ancient philosophical schools in Late Antiquity. This luxurious 4th century residence in Belgian Gaul was home to an exceptional series of hermae busts that surrounded a very large basin. Scholars and great military men made up a collection of 68 portraits, the diversity and erudition of which somewhat make up for the mediocre quality of the sculptures. Socrates in included in this group H. Wrede, Die Spätantike Hermengalerie von Welschbillig : Untersuchung zur Kunsttradition im 4. Jahrhundert n. Chr. und zur allgemeinen Bedeutung des antiken Hermenmals (Römisch-germaische Kommission des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts zu Frankfurt A.M. Römisch-Germanische Forschungen), Berlin, 1972, pp. 46-54..

Villa Welschbillig (Rhineland-Palatinate), is yet another example of the importance given to the ancient philosophical schools in Late Antiquity. This luxurious 4th century residence in Belgian Gaul was home to an exceptional series of hermae busts that surrounded a very large basin. Scholars and great military men made up a collection of 68 portraits, the diversity and erudition of which somewhat make up for the mediocre quality of the sculptures. Socrates in included in this group H. Wrede, Die Spätantike Hermengalerie von Welschbillig : Untersuchung zur Kunsttradition im 4. Jahrhundert n. Chr. und zur allgemeinen Bedeutung des antiken Hermenmals (Römisch-germaische Kommission des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts zu Frankfurt A.M. Römisch-Germanische Forschungen), Berlin, 1972, pp. 46-54..

The mosaics of rich homes also reveal that similar iconographic themes were popular among owners. In Germany, the stone flooring discovered in the cathedral in Cologne and dated back to the end of the Severan period, represents a series of pentagons featuring philosophers, along with their names, written in Greek. Diogenes, in the middle, rubs shoulders with Socrates in particular. Yet unlike the statuary found in Chiragan, here, only the inscription, and not the physical attributes, identify the master, who is represented as a conventional and stereotypical scholar M. Lucciano, « Les représentations iconographiques de Socrate, » Camenae, 10, 2012, en partic. p. 11-12, ill. 1..

In short, although the Philosophers’ relief has been linked to the High Roman Empire, the second half of the 2nd century or, more broadly, between the 2nd and 3rd centuries, D. Cazes et al., Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris, 1999, p. 117., its date is in fact more recent, and the panel is to be associated with later productions. It thus joins the main corpus of sculptures made from Saint-Béat marble that characterised the villa from the end of the 3rd century, if not the first third of the 4th.

P. Capus

Bibliography

- Ensoli, La Rocca 2000 S. Ensoli, E. La Rocca (eds.), Aurea Roma : dalla città pagana alla città cristiana. Mostra, Palazzo delle esposizioni, Roma, 22 dicembre 2000-20 aprile 2001, Rome. p. 457-458, no 53

- Beckmann 2020 S.E. Beckmann, « The Idiom of Urban Display: Architectural Relief Sculpture in the Late Roman Villa of Chiragan (Haute-Garonne), » American Journal of Archaeology, 124, 1, pp. 133–160. p. 142-144, fig. 10

- Bergmann 1999 M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden. p. 33, 36, 69, pl. 1, 3-5, 10

- Bergmann 1995 M. Bergmann, « Un ensemble de sculptures de la villa romaine de Chiragan, oeuvre de sculpteurs d’Asie Mineure, en marbre de Saint-Béat ?, » J. Cabanot, R. Sablayrolles, J.-L. Schenck (eds.), Les marbres blancs des Pyrénées : approches scientifiques et historiques. Colloque, 14-16 octobre 1993, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, pp. 197–205. p. 197-205

- Cazes et al. 1999 D. Cazes, E. Ugaglia, V. Geneviève, L. Mouysset, J.-C. Arramond, Q. Cazes, Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris. p. 117

- Dillon 2006 S. Dillon, Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture : Contexts, Subjetcs and Styles, Cambridge.

- Dontas 1960 G. Dontas, « Eikones kathemenôn pneumatikôn anthrôpôn, » pp. 22–24.

- Du Mège 1835 A. Du Mège, Description du musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 95, no 182

- Espérandieu 1908 É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, 2. Aquitaine, Paris. p. 59, no 946

- Hannestad 1994 N. Hannestad, Tradition in Late Antique Sculpture : Conservation, Modernization, Production (Acta Jutlandica. Humanities Series), Aarhus. p. 128

- Hermary 1996 A. Hermary, « Socrate à Toulouse, » Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise, 29, 1, pp. 21–30. p. 26-30

- Joulin 1901 L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris. fig. 193 B et D

- Lebègue 1891 A. Lebègue, « Notice sur les fouilles de Martres, » Revue des Pyrénées et de la France méridionale, pp. 573–611. p. 416, pl. 27, 2

- Lippold 1912 G. Lippold, Griechische Porträtstatuen, Munich. p. 54

- Massendari 2006 J. Massendari, La Haute-Garonne : hormis le Comminges et Toulouse 31/1 (Carte archéologique de la Gaule), Paris. p. 258, fig. 146

- Rachou 1912 H. Rachou, Catalogue des collections de sculpture et d’épigraphie du musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. no 116

- Richter 1965 G.M.A. Richter, The Portraits of the Greeks. I, Introduction. The Early Period. The Fifth Century, London. p. 118

- Roschach 1865 E. Roschach, Catalogue des antiquités et des objets d’art, Toulouse. p. 24-25, no 31

- Scheibler 1989 I. Scheibler, Sokrates in der griechischen Bildkunst. Sonderausstellung der Glyptothek und des Museums für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke, 12. Juli bis 24. September 1989, Munich. p. 80

- Bulletin municipal Toulouse 1936 Bulletin municipal Toulouse, Bulletin municipal, Toulouse. p. 831

To cite this notice

Capus P., "Assembly of philosophers (?)", in The sculptures of the roman villa of Chiragan, Toulouse, 2019, online <https://villachiragan.saintraymond.toulouse.fr/en/ark:/87276/a_ra_116_ra_95>.