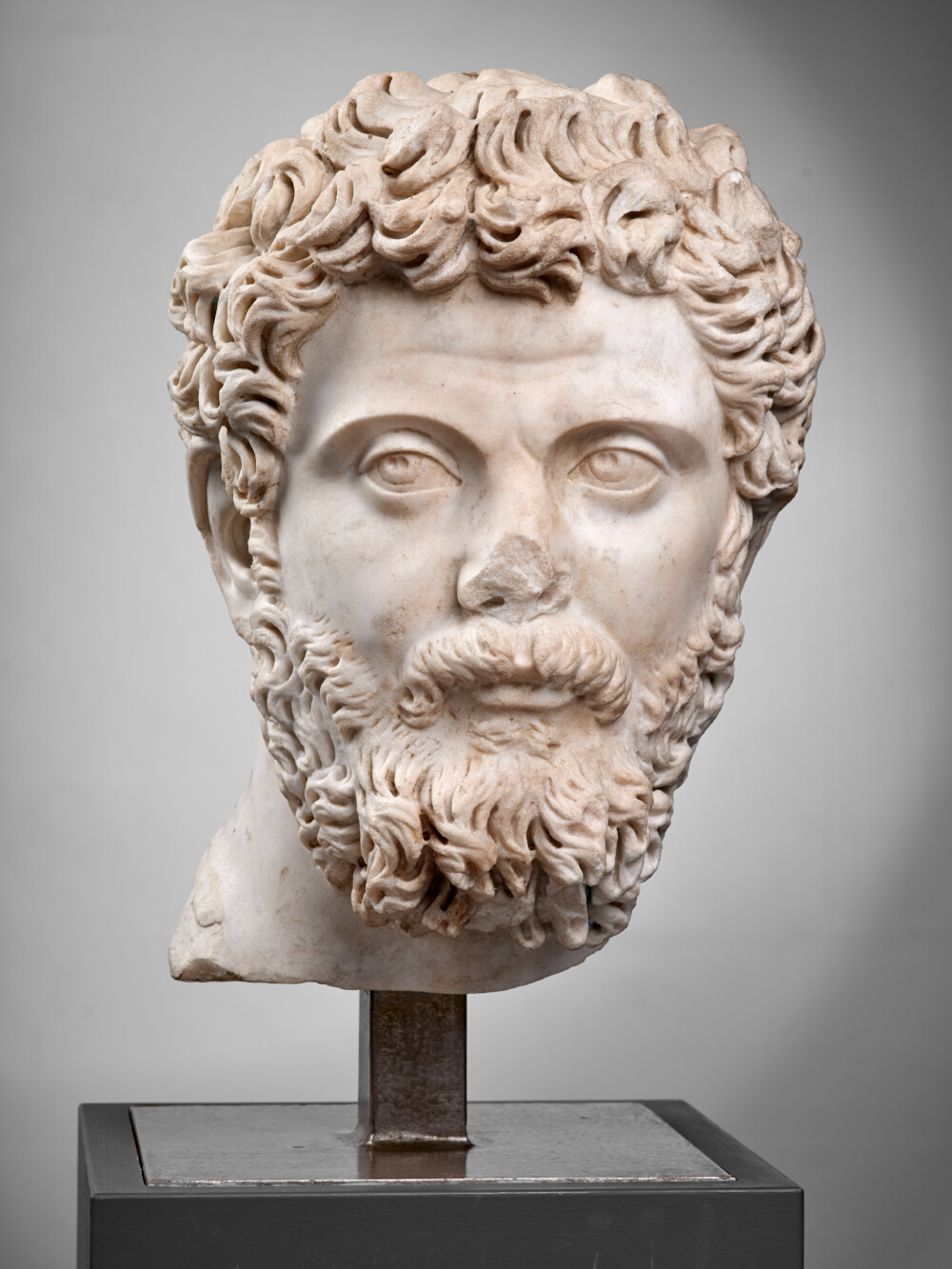

Head of Septimius Severus

- Biographic data

- 145 - 211

Emperor from 193 to 211 - Date de création

- Between 193 and 195

- Type

- Of the "advent" type

- Material

- Göktepe marble, district 3 (Turkey)

- Dimensions

- H. 34 x l. 24 x P. 24 (cm)

- Inventory number

- Ra 120 a

- Photo credits

- Daniel Martin

Septimius Severus, a senator born in Leptis Magna (in Tripolitania, modern-day Libya) in the Roman province of Africa, went on to become the governor of the province of Pannonia Superior, in the heart of Europe. Following the assassination of Emperor Commodus, then of Pertinax, he was made emperor by the legions of the Danube. With the support of his armies, he marched on Rome to establish his legitimacy and eliminate his main rivals.

This outstanding head, designed in an official workshop in Rome, dates from his accession to power in AD 193, a year that brought a number of political twists and turns. On the 28th March, Pertinax was assassinated after only eighty-seven days of reign. This event ushered in a period of unrest, similar to that experienced throughout the Empire in 69 following the elimination of Nero. In Rome, on the day of Pertinax’s death, Didius Julianus was proclaimed emperor by the praetorians and Senate; but on the 9th April, the legions of Pannonia Superior invested Septimius Severus, the governor of the province, with imperial dignity, and two months later he was in Rome, where the Senate had finally acknowledged him, and where Didius Julianus had just been murdered. In the East, the governor of Syria, Pescennius Niger, who had also been elevated to Augustus by his troops in April 193, had set off for Rome. Severus went to meet him, defeated him near Cyzicus (on the southern coast of the Sea of Marmara, ancient Propontius) and then returned to Rome where the announcement of a new rebellion awaited him, that of Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britain, whom he had however designated as Caesar in April 193, and with whom he had shared the consulate in 194. Declared a public enemy (hostis) in December 195, Albinus was beaten in Lyon in February 197, and killed while attempting to flee.

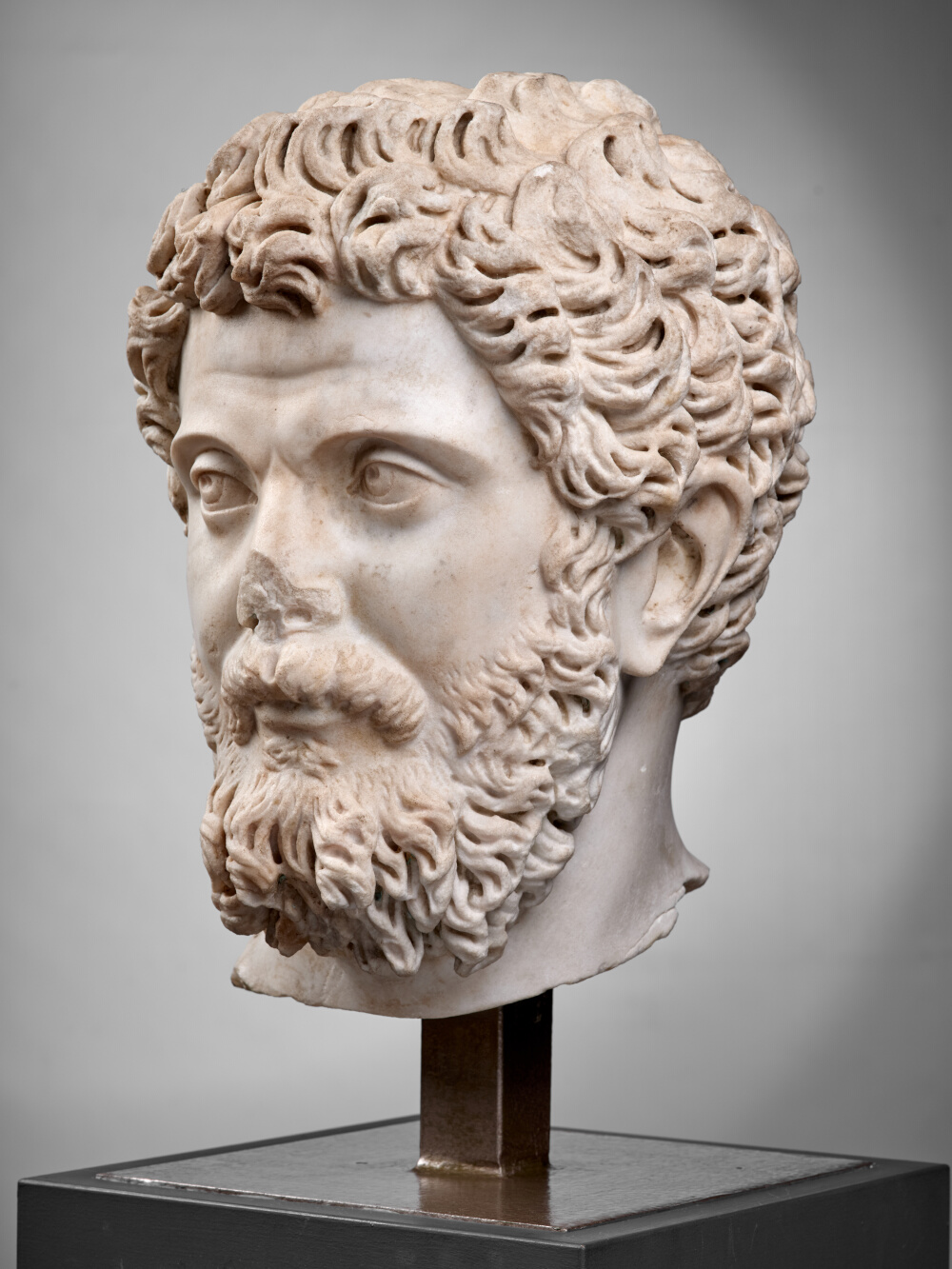

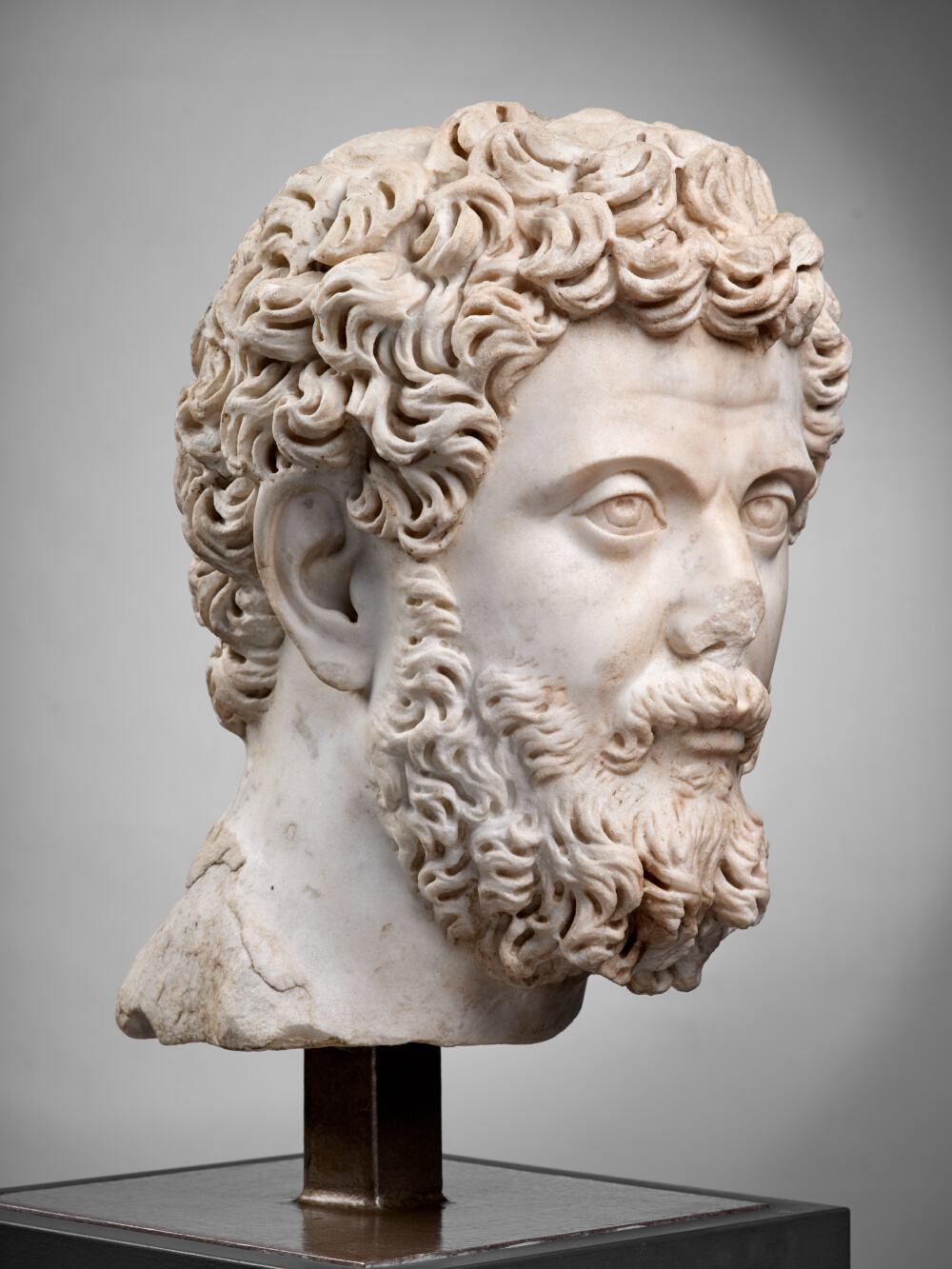

This portrait discovered in Chiragan corresponds to « Type I » of the Emperor’s portraits. Septimius Severus was 38 years old at the time. The hairstyle and beard are short, and there are three curls on his forehead. His gaze is directed upwards, and his head is turned to the right. The head, which is beautifully made, belongs to a group of five portraits, all of which testify, down to the very last detail, to the existence of a common original. They are kept in Toronto (Royal Ontario Museum, inv. 933.27.4), Toulouse (Musée Saint-Raymond, inv. Ra 120 a), Saint Petersburg (Hermitage Museum, A 3184), London, Bonhams Antiquities (sale dated 3rd April 2014) and Melbourne (National Gallery of Victoria, inv. 1490/56). The  Toronto copy, which originated in Ostia, is the most well-preserved. To complete this group of five portraits, there is also a colossus head from Turkey (Istanbul Archaeological Museums, inv. 46), crowned with oak leaves, as well as a head wearing a crown of laurel leaves in Tyre, now kept at the museum in Beirut (National Museum, inv. DGA 13204). The discrepancies observed in these last two portraits can be explained by the different practices implemented by oriental workshops, but also by the difficulties that must have been encountered in disseminating this first image of the emperor throughout the provinces.

Toronto copy, which originated in Ostia, is the most well-preserved. To complete this group of five portraits, there is also a colossus head from Turkey (Istanbul Archaeological Museums, inv. 46), crowned with oak leaves, as well as a head wearing a crown of laurel leaves in Tyre, now kept at the museum in Beirut (National Museum, inv. DGA 13204). The discrepancies observed in these last two portraits can be explained by the different practices implemented by oriental workshops, but also by the difficulties that must have been encountered in disseminating this first image of the emperor throughout the provinces.

In these portraits, based on Septimius Severus’s first iconographic type, the hair is considerably shorter and closer to the skull than in the following two types, which portrays him with long, puffy locks around the temples, a smoother forehead, less pronounced eyebrows, and uncovered ears, all of which completely alters his appearance. This is indeed the soldier emperor who is depicted here, waging a war against those vying for the Empire, whereas the following types were to have a completely different meaning. When comparing them, it is important to note the gaze, which is keener and looking in the opposite directions, making this emperor a man of action. The « advent » type shows him looking to the right, but not yet upwards, as in some specimens of the « adoption » and « Serapis » types, which confirm his close contact with the gods.

According to J.-C. Balty 2020, Les Portraits Romains : L’époque des Sévères, Toulouse, p. 85-93.

Bibliography

- Balty 1966 J. Balty, Essai d’iconographie de l’empereur Clodius Albinus (Collection Latomus), Brussels. p. 38, no 9

- Balty 1964 J. Balty, « Les premiers portraits de Septime Sévère : Problèmes de méthode, » Latomus, 23, 1, pp. 56–63. p. 60-61, no 7

- Balty, Cazes 2021 J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : L’époque des Sévères, 1.3 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse. p. 61, 85-93

- Balty, Cazes, Rosso 2012 J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, E. Rosso, Les portraits romains, 1 : Le siècle des Antonins, 1.2 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse. p. 66, fig. 62, p. 264, fig.195

- Braemer 1952 F. Braemer, « Les portraits antiques trouvés à Martres-Tolosane, » Bulletin de la Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France, pp. 143–148. p. 145

- Cazes et al. 1999 D. Cazes, E. Ugaglia, V. Geneviève, L. Mouysset, J.-C. Arramond, Q. Cazes, Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris. p. 128

- Espérandieu, Lantier 1907 É. Espérandieu, R. Lantier, Recueil général des bas-reliefs, statues et bustes de la Gaule romaine, 1 (Collection de documents inédits sur l’histoire de France), Paris. p. 68, no 963

- Felletti Maj 1953 B.M. Felletti Maj, Museo nazionale romano : i ritratti (Cataloghi dei musei e gallerie d’Italia), Rome. p. 128

- Joulin 1901 L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris. p. 337, pl. XXII, no 294 D

- McCann 1968 A.M. McCann, The Portraits of Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211) (Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome), Rome. p. 135-136, no 14, pl. XXXIII a-b

- Poulsen 1928 F. Poulsen, Porträtstudien in norditalienischen Provinzmuseen, Copenhagen. p. 27, no 1

- Rachou 1912 H. Rachou, Catalogue des collections de sculpture et d’épigraphie du musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 60, no 120

- Rosso 2006 E. Rosso, L’image de l’empereur en Gaule romaine : portraits et inscriptions (Archéologie et histoire de l’art), Paris. p. 468-470, no 225

- Saastamoinen 2009 A. Saastamoinen, Afrikan loistavat kaupungit. Elämä roomalaisajan Pohjois-Afrikassa, Helsinki. p. 38

- Soechting 1972 D. Soechting, Die Porträts des Septimus Severus (Habelts Dissertationsdrucke. Reihe klassische Archäologie), Bonn. p. 146, no 23, pl. 3 c-d

- von Heintze 1966 H. von Heintze, « Studien zu den Porträts des 3. Jahrhunderts n. Chr., 7. Caracalla, Geta, Elagabal und Severus Alexander, » Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung (MDAIR), 66, 73-74, pp. 190–231. p. 198, no 42, no 3

- Musée Saint-Raymond 1995 Musée Saint-Raymond, Le regard de Rome : portraits romains des musées de Mérida, Toulouse et Tarragona. Exhibition, Mérida, Museo nacional de arte romano ; Toulouse, Musée Saint-Raymond ; Tarragone, Museu nacional arqueològic de Tarragona, 1995, Toulouse. p. 173

- Bulletin municipal Toulouse 1936 Bulletin municipal Toulouse, Bulletin municipal, Toulouse. p. 831

To cite this notice

Capus P., "Head of Septimius Severus", in The sculptures of the roman villa of Chiragan, Toulouse, 2019, online <https://villachiragan.saintraymond.toulouse.fr/en/ark:/87276/a_ra_120_a>.