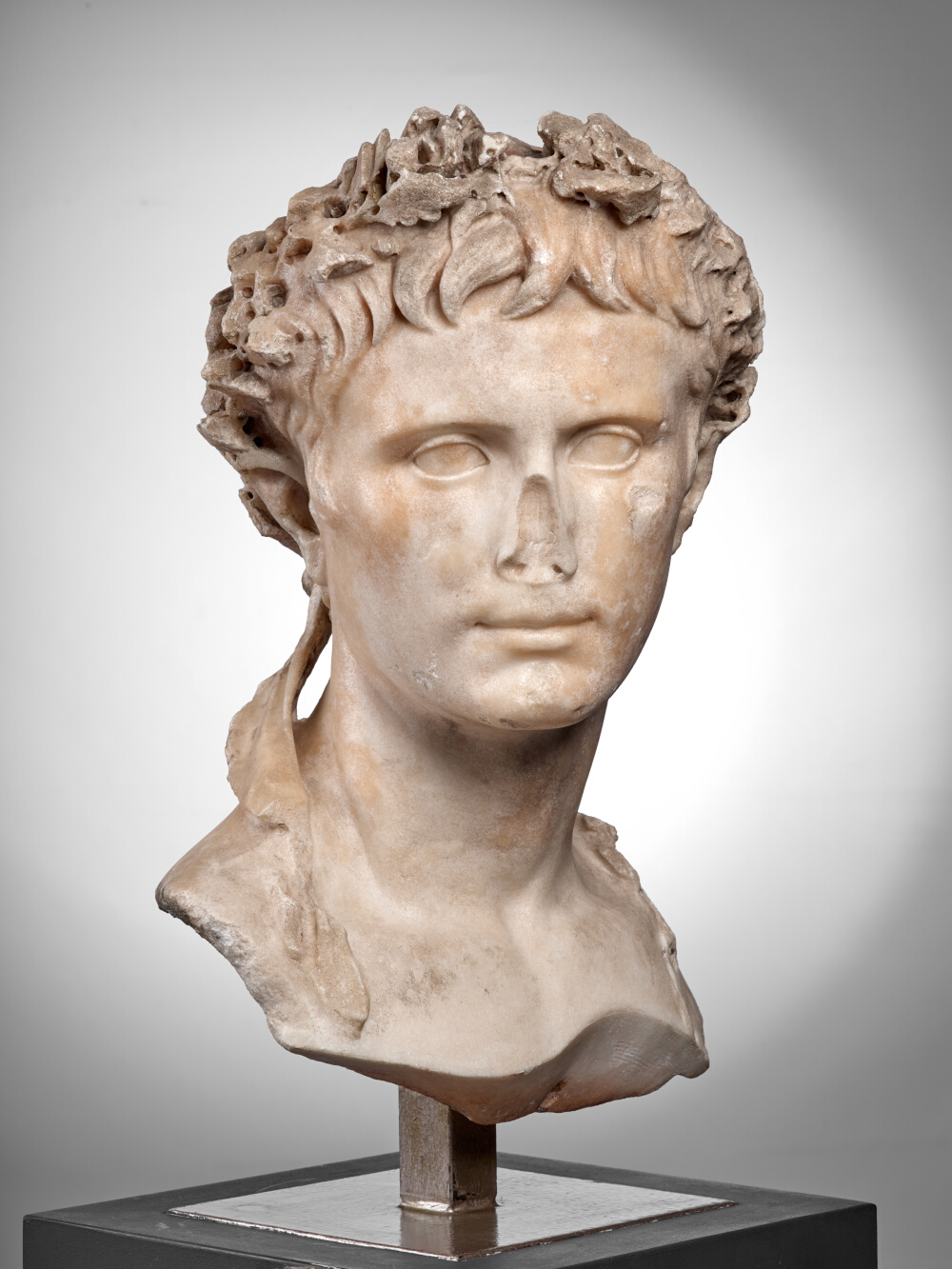

Bust of Augustus crowned with oak leaves

- Biographic data

- 63 BC – AD 14.

Emperor from 27 BC to AD 14 - Date de création

- First half of the 1st century

- Type

- Known as "of the Prima Porta type"

- Material

- Lychnites marble (island of Paros)

- Dimensions

- H. 51 x l. 34 x P. 25 (cm)

- Inventory number

- Ra 57

- Photo credits

- Daniel Martin

Octavian, grandnephew of Julius Caesar, is the saviour of the Republic and founder of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. He was elevated to Augustus (an epithet that refers to the religious sphere, and raises the beneficiary above other men) by the Senate on the 16th January 27 BC. Augustus soon became his first name, and that of all his successors.

The manner in which his forehead locks are depicted is identical to that of the head, associated with a barefooted body wearing a cuirass, of the  statue of Augustus discovered in Prima Porta on the outskirts of Rome, in the villa that belonged to his wife Livia. This statue, now kept in the Vatican Museums, shows a face which, far from the physiognomy of the emperor, was inspired by that of the Doryphoros (« spear bearer »), a bronze sculpture known from some Roman marble replicas sculpted around 440 BC by Polykleitos, one of the great masters of Classical Antiquity. Art in Greece in the 5th century BC was indeed a constant reference point in Augustan art. The Greek ideal was seen as a way of giving the eternally young emperor an unchanging image that reflected the stability of the Empire. The iconographic genre of the head of the Prima Porta statue is associated with a statuary type that is symbolically highly significant: bare feet, which undoubtedly referred to a religious context or to heroism, and a decorated breastplate showing the restitution, in 20 BC, of the standards taken by the Parthians from the Roman legions of Crassus during the battle of Carrhae (present-day Turkey), in 53 BC. As we know, only one type of portrait, constantly reproduced and unchanging, could be associated with different types of statues: wearing a cuirass, a toga (bare headed or veiled), a bare torso with a mantle rolled at the waist, sitting or on horseback. The portrait of Augustus, which is therefore identical to that of the Prima Porta statue kept at the Vatican, boasts a hairstyle that departs, from the norm previously adopted to represent the Emperor, especially in the depiction of the hair above the forehead. It shows the same hairstyle that had been strictly adhered to throughout his reign, determined by long strands of hair swept from right to left to form a fork, and « crab claw »-shaped strands of hair. The hairstyle is flatter, with less volume than in more youthful portraits designed during the civil war. The present features are marked by the balance and fulfilment that are inherent to classic Greek art, in keeping with the carefully disciplined hair, both being a metaphor for the Pax Romana insured by the avenger of Caesar’s death. This type of portrayal, which was to remain unchanged, was a way of unequivocally identifying the primus inter pares (first among equals). From the moment he became known as Augustus and seized power within the Republic (without there being any real question of a monarchical type of regime) in 27 BC, this portrait of the imperator was created and asserted. This ideal image was then rapidly disseminated throughout the length and breadth of the Empire.

statue of Augustus discovered in Prima Porta on the outskirts of Rome, in the villa that belonged to his wife Livia. This statue, now kept in the Vatican Museums, shows a face which, far from the physiognomy of the emperor, was inspired by that of the Doryphoros (« spear bearer »), a bronze sculpture known from some Roman marble replicas sculpted around 440 BC by Polykleitos, one of the great masters of Classical Antiquity. Art in Greece in the 5th century BC was indeed a constant reference point in Augustan art. The Greek ideal was seen as a way of giving the eternally young emperor an unchanging image that reflected the stability of the Empire. The iconographic genre of the head of the Prima Porta statue is associated with a statuary type that is symbolically highly significant: bare feet, which undoubtedly referred to a religious context or to heroism, and a decorated breastplate showing the restitution, in 20 BC, of the standards taken by the Parthians from the Roman legions of Crassus during the battle of Carrhae (present-day Turkey), in 53 BC. As we know, only one type of portrait, constantly reproduced and unchanging, could be associated with different types of statues: wearing a cuirass, a toga (bare headed or veiled), a bare torso with a mantle rolled at the waist, sitting or on horseback. The portrait of Augustus, which is therefore identical to that of the Prima Porta statue kept at the Vatican, boasts a hairstyle that departs, from the norm previously adopted to represent the Emperor, especially in the depiction of the hair above the forehead. It shows the same hairstyle that had been strictly adhered to throughout his reign, determined by long strands of hair swept from right to left to form a fork, and « crab claw »-shaped strands of hair. The hairstyle is flatter, with less volume than in more youthful portraits designed during the civil war. The present features are marked by the balance and fulfilment that are inherent to classic Greek art, in keeping with the carefully disciplined hair, both being a metaphor for the Pax Romana insured by the avenger of Caesar’s death. This type of portrayal, which was to remain unchanged, was a way of unequivocally identifying the primus inter pares (first among equals). From the moment he became known as Augustus and seized power within the Republic (without there being any real question of a monarchical type of regime) in 27 BC, this portrait of the imperator was created and asserted. This ideal image was then rapidly disseminated throughout the length and breadth of the Empire.

The statue found in Chiragan wears a corona civica (« civic crown »), in the form of a chaplet of oak leaves, symbol of Jupiter. This honorary emblem was awarded by the Senate in 27 BC, during the investiture ceremony of the one who had put an end to the civil wars, restored peace and ensured the preservation of the values of the oligarchic Republic. Two other portraits of the same type, and also crowned with oak leaves, kept in the  Louvre Museum and the

Louvre Museum and the  Munich Glyptothek, have been likened to the head unearthed in Chiragan. In all three works, as in many others, the fact that the skull is flattened at the back is particularly noteworthy; it would seem that this recurring feature found on marble portraits of the emperor represents one of his actual physical attributes, in the same way as the bump on the bridge of the nose, as reported by Suetonius Suétone, « Auguste, » Vies Des Douze Césars, beginning of the 2nd century. in his detailed description of Augustus.

Munich Glyptothek, have been likened to the head unearthed in Chiragan. In all three works, as in many others, the fact that the skull is flattened at the back is particularly noteworthy; it would seem that this recurring feature found on marble portraits of the emperor represents one of his actual physical attributes, in the same way as the bump on the bridge of the nose, as reported by Suetonius Suétone, « Auguste, » Vies Des Douze Césars, beginning of the 2nd century. in his detailed description of Augustus.

According to J.-C. Balty 2005, Les portraits romains, 1 : Époque julio-claudienne, 1.1 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse, p. 73-98.

Bibliography

- Balty, Cazes 2005 J.-C. Balty, D. Cazes, Les portraits romains, 1 : Époque julio-claudienne, 1.1 (Sculptures antiques de Chiragan (Martres-Tolosane), Toulouse. p. 45-47, fig. 16-17, p. 75-98, fig. p. 74, 76, 78, 81 no 7, 83 no 10, 86 no 16, 89 no 21, 90, 92-93, 96 no 26

- Benoit 1952 F. Benoit, « Le sanctuaire d’Auguste et les cryptoportiques d’Arles, » Revue archéologique, 39. p. 38

- Bergmann 1999 M. Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodisias, Konstantinopel : zur mythologischen Skulptur der Spätantike (Palilia), Wiesbaden. p. 28, no 142

- Bernoulli 1882 J.J. Bernoulli, Römische Ikonographie, Stuttgart. II : Die Bildnisse der römischen Kaiser. 3 : Von Pertinax bis Theodosius, p. 39, no 61

- Boschung 1993 D. Boschung, Die Bildnisse des Augustus (Das römische Herrscherbild. 1. Abteilung), Berlin. p. 44, 86, 102, no 61-62, 138, 142, 158, 163, 168, 494, cat. no 199 p. 190, pl. 166.1-4, 223.2

- Boschung 2002 D. Boschung, Gens Augusta : Untersuchungen zu Aufstellung, Wirkung und Bedeutung der Statuengruppen des julisch-claudischen Kaiserhauses (Monumenta artis romanae), Mainz. no 45.1, p. 128, 131, pl. 95.1

- Braemer 1999 F. Braemer, « Le culte impérial en Narbonnaise et dans les Alpes au Haut-Empire : documents sculptés, » Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise, 32, pp. 49–55. p. 54, fig. 3

- Braemer 1952 F. Braemer, « Les portraits antiques trouvés à Martres-Tolosane, » Bulletin de la Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France, pp. 143–148.

- Cazes et al. 1999 D. Cazes, E. Ugaglia, V. Geneviève, L. Mouysset, J.-C. Arramond, Q. Cazes, Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris. p. 118 et fig.

- Curtius 1935 L. Curtius, Ikonographische Beiträge zum Porträt der Römischen Republik und der Julisch-Claudischen Familie : VII Nero Claudius Drusus, der Ältere VIII Jugendbildnisse des Tiberius (Römische Mitteilungen), Berlin. p. 281

- Du Mège 1835 A. Du Mège, Description du musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 98-99, nº 188

- Du Mège 1828 A. Du Mège, Notice des monumens antiques et des objets de sculpture moderne conservés dans le musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 60-61, nº120

- Du Mège 1830 A. Du Mège, « Recherches sur Calagorris des Convenae, » Mémoires de l’Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Belles-lettres de Toulouse, t. II 1823-1827.

- Espérandieu 1908 É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, 2. Aquitaine, Paris. p. 60, no 948

- Frigerio 1938 F. Frigerio, « Augusto, gesta e immagini, » Rivista Archeologica dell’antica Provincia e Diocesi di Como, CXVII-CXVIII. p. 49, fig. 25

- Gonse 1904 L. Gonse, Les chefs-d’oeuvre des musées de France : Sculpture, dessins, objets d’art, Paris. p. 330 et fig.

- Hausmann 1981 U. Hausmann, « Zur Typologie und Ideologie des Augustus-porträts, » Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, Berlin-New York. p. 583-584, no 261

- Hertel 1982 E.D. Hertel, Untersuchungen zu Stil und Chronologie des Kaiser-und Prinzenporträts von Augustus bis Claudius, Bonn. p. 66, no 127, p. 271

- Johansen 1976 F. Johansen, « Le portrait d’Auguste de Prima Porta et sa datation, » Studia Romana in honorem Petri Krarup septuagenarii, Odense, p. 57. p. 57, no 23

- Joulin 1901 L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris. p. 115, pl. XVIII, no 255 b, 256 b

- Massendari 2006 J. Massendari, La Haute-Garonne : hormis le Comminges et Toulouse 31/1 (Carte archéologique de la Gaule), Paris. ill. de couv., p. 242, fig. 100

- Montini 1938 I. Montini, Il Ritratto di Augusto, Rome. p. 51-52, p. 93, no 118

- Rachou 1912 H. Rachou, Catalogue des collections de sculpture et d’épigraphie du musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 41, no 57

- Roschach 1865 E. Roschach, Catalogue des antiquités et des objets d’art, Toulouse. p. 32, nº 57

- Rosso 2006 E. Rosso, L’image de l’empereur en Gaule romaine : portraits et inscriptions (Archéologie et histoire de l’art), Paris. p. 448-450, no 213

- Salviat, Terrer 1980 F. Salviat, D. Terrer, « À la découverte des empereurs romains et de leur famille, à travers les historiens et les portraits de Gaule Narbonnaise, » Les dossiers de l’archéologie, 41, pp. 6–87. p. 22-25

- Musée Saint-Raymond 1990 Musée Saint-Raymond, Le cirque romain. Exhibition, Musée Saint-Raymond, Toulouse, 1990, Toulouse.

- Musée Saint-Raymond 2011 Musée Saint-Raymond, L’essentiel des collections (Les guides du MSR), Toulouse. p. 40-41

- Musée Saint-Raymond 1995 Musée Saint-Raymond, Le regard de Rome : portraits romains des musées de Mérida, Toulouse et Tarragona. Exhibition, Mérida, Museo nacional de arte romano ; Toulouse, Musée Saint-Raymond ; Tarragone, Museu nacional arqueològic de Tarragona, 1995, Toulouse. p. 39, no 1

- Musée archéologique Henri Prades 1990 Musée archéologique Henri Prades, Le cirque et les courses de chars, Rome-Byzance. Exhibition, Musée archéologique Henri Prades, Lattes, 1990, Lattes.

To cite this notice

Capus P., "Bust of Augustus crowned with oak leaves", in The sculptures of the roman villa of Chiragan, Toulouse, 2019, online <https://villachiragan.saintraymond.toulouse.fr/en/ark:/87276/a_ra_57>.