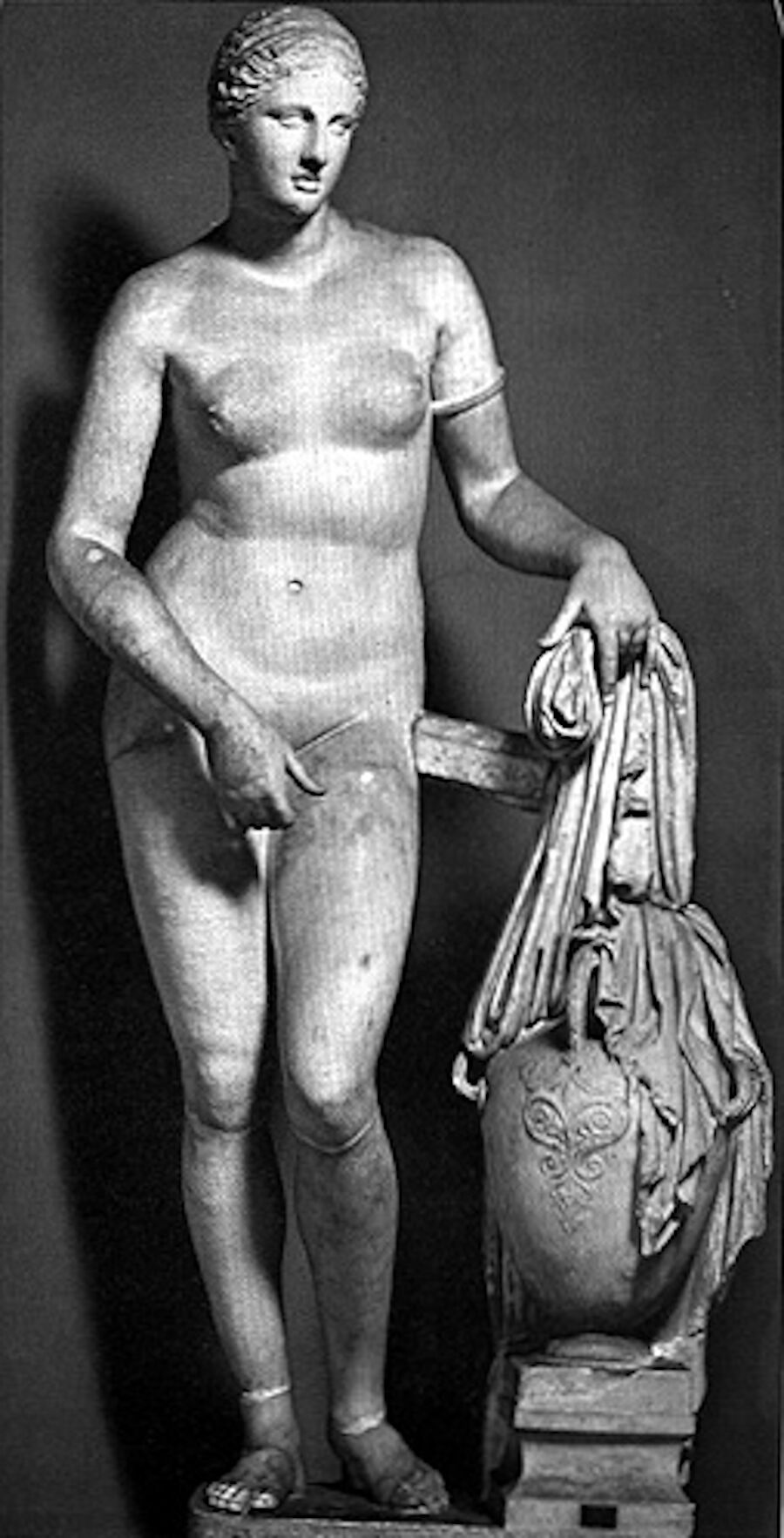

Head of Venus

- Date de création

- 1st-2nd century

- Material

- Lychnites marble (island of Paros)

- Dimensions

- H. 40 x l. 24 x P. 31 (cm)

- Inventory number

- Ra 52

- Photo credits

- Daniel Martin

Excavations in 1826 unearthed this remarkable head of Aphrodite or Venus as she was called by the Romans. The lower edge ends at the top of the sternum, at the manubrium, and includes the start of the left shoulder. In spite of the cleaning process, which was often excessive in the 19th century, a few limestone concretions remain on the left side, and especially in the hair, as described by the Count of Clarac, Curator of Antiquities at the Louvre, who saw the head shortly after it was discovered F. Clarac, Musée de sculpture antique et moderne ou Description historique et graphique du Louvre et de toutes ses parties : des statues, bustes, bas-reliefs et inscriptions du Musée royal des Antiques et des Tuileries, et de plus de 2500 statues antiques … tirées des principaux musées et des diverses collections de l’Europe… accompagnée d’une iconographie égyptienne, grecque et romaine…. Tome II, Paris, 1841, p. 588.. The posterior part forms a pitted protrusion that is characteristic of an embedding plug that allows us to assume that the head was inserted into the body of a statue. Yet the fragments were not found in the museum’s reserves, despite Alexandre Du Mège’s mention of « portions of arms that appear to have been part of this statue » A. Du Mège, Description du musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse, 1835, p. 79, no 140.. It may also have been fitted to a bust or even a herma (pillar).

The work became so famous that it was named « The Venus de Martres », which set it apart and bore witness to the prestige that had been bestowed on it. The expert and discerning eye of the Count of Clarac considered this Venus to be « one of the loveliest of all, if not the most beautiful », when compared to those of  Medici,

Medici,  Arles and

Arles and  Milo, all of which were the ultimate references in the first half of the neo-classical 19th century. Exhibited in Paris in 1867, this statue was attributed to the Greek Praxiteles F. Pagès, « La Vénus de Martres, » Revue archéologique du Midi de la France, 2, 1867, pp. 50–52. before being more reasonably seen as one of the replicas of the Aphrodite of Knidos, the coastal town of Caria (south-western modern-day Turkey). Although the original work created around 360 BC has since disappeared, it was copied extensively. Its reputation owes much to the testimony of Pliny the Elder, who described the sculptor in the following words: « His Venus towers above not only his previous work, but also the works of all the artists in the world » Pline l’Ancien, Histoire naturelle, 77 (circa), XXXVI, 20.. The same Pliny reports that if Praxiteles had been given the opportunity to select one of his works, the artist would, without hesitation, have chosen « those which had been touched by the hands of Nicias ». The latter had indeed mastered the art of applying colours to the polished marble sculptures, and primarily those created by his fellow-artist Praxiteles.

Milo, all of which were the ultimate references in the first half of the neo-classical 19th century. Exhibited in Paris in 1867, this statue was attributed to the Greek Praxiteles F. Pagès, « La Vénus de Martres, » Revue archéologique du Midi de la France, 2, 1867, pp. 50–52. before being more reasonably seen as one of the replicas of the Aphrodite of Knidos, the coastal town of Caria (south-western modern-day Turkey). Although the original work created around 360 BC has since disappeared, it was copied extensively. Its reputation owes much to the testimony of Pliny the Elder, who described the sculptor in the following words: « His Venus towers above not only his previous work, but also the works of all the artists in the world » Pline l’Ancien, Histoire naturelle, 77 (circa), XXXVI, 20.. The same Pliny reports that if Praxiteles had been given the opportunity to select one of his works, the artist would, without hesitation, have chosen « those which had been touched by the hands of Nicias ». The latter had indeed mastered the art of applying colours to the polished marble sculptures, and primarily those created by his fellow-artist Praxiteles.

Comparative studies of the dozens of listed replicas of the statue, considered to be one of the pinnacles of sculpture in the second classical period in Greece, have both cast doubt on the actual appearance of Praxiteles’ masterpiece, and sharpened our appreciation of his various copies or variants. Thus, the descriptive information provided by some ancient authors, and the reproduction of the sculpture on the coins of Knidos, must be compared and evaluated in relation to all the replicas from the Hellenistic and Roman period, which are likely to provide us with a more or less faithful copy.

It is known that the naked body of the goddess had initially surprised and even shocked those who saw it. So much so in fact, that the people of Kos, neighbours and rivals of those of Knidos, refused the statue they had commissioned for their temple. They ceded it to the Knidians, who were perhaps more daring, but who appear to have substituted it for an already naked religious effigy of Eastern tradition mainly devoted to fertility. Moreover, this petrified body was in no way hidden. It was installed in a mainly open chapel, a small circular temple built within a sacred enclosure planted with myrtles, cypresses, plane trees and vines. Aphrodite’s right hand hovers in front of her pubic area, a gesture interpreted as an act of modesty, as if she had been surprised in a moment of intimacy, but meant to allow the goddess of fertility to draw attention to her reproductive organs. Her left hand holds a cloth draped over a bronze hydra. The presence of this vessel is an unambiguous indication that Aphrodite is bathing, which means that her slightly tilted bust may have been reflected in a washbasin. This composition, which was more than a simple genre scene depicting Aphrodite surprised while bathing, probably referred to the ritual nature of ablutions.

Something of the mystery behind this face, body and attitude still imbues the most beautiful replicas that have survived to this day. The forward-tilted head found in Martres reminds us of the graceful angle of the head of the Knidian Venus. The chignon at the back of her head reveals the graceful line of her neck, which in turn echoes the slope of her back. Long wavy strands of hair are divided by a middle parting and held in place by a smooth double band that encircles her skull. Does this band allude to Aphrodite’s own embroidered band or kestos himas (« rolled belt »)? This cestus veneris made the goddess irresistible, and an object of desire for anyone who approached her. Except for her slightly asymmetrical eyes, her features are regular. And unlike the harsh features of certain replicas, such as the head of the  Borghese Venus in the Louvre, or the

Borghese Venus in the Louvre, or the  Colonna Venus at the Vatican, which most art historians consider to be closer to Praxiteles’ work, the features of the Venus of Martres, or those of the

Colonna Venus at the Vatican, which most art historians consider to be closer to Praxiteles’ work, the features of the Venus of Martres, or those of the  Kaufmann head in the Louvre, seem less harsh and more subtly softened. Lifelike skin and full lips make her more sensual. Yet while she may seem more human, her sanctity remains obvious, despite her expression, which seems to be in the act of drifting into a tender dreamlike state.

Kaufmann head in the Louvre, seem less harsh and more subtly softened. Lifelike skin and full lips make her more sensual. Yet while she may seem more human, her sanctity remains obvious, despite her expression, which seems to be in the act of drifting into a tender dreamlike state.

Although the Kaufmann head, discovered in Tralles in Turkey, and dating back to the 2nd century BC, could be seen as a reinterpretation of the Hellenistic period, A. Pasquier, La Vénus de Milo et les Aphrodites du Louvre (Albums), Paris, 1985, pp. 58-59., it is impossible to date the Venus of Martres with the same degree of accuracy. Its marble, analysed in 2011, is indeed Greek, and comes from Paros. This alone cannot be used as an argument to date the work, as Aegean Island marbles were still being used throughout the High Roman Empire. At the most, one could venture a date before the second half of the 2nd century AD. It has been suggested that it was probably made during the middle of the 1st century AD, and by an oriental workshop F. Slavazzi, Italia verius quam provincia : diffusione e funzioni delle copie di sculture greche nella Gallia Narbonensis (Aucnus), Naples, 1996, pp. 186-187.. It is a well-known fact that during the first two centuries AD, the great classics of Greek art became very popular in the imperial sphere, as well as in some luxurious Italian or provincial estates. And it appears that Chiragan did not ignore this trend, as can be seen by the small marble tablets related to the so-called neo-Attic artistic movement, the two figures of Athena, as well as a whole series of small artefacts that are replicas, or variants, of Greek originals.

P. Capus

Bibliography

- Bassal 1996 A. Bassal, « Vénus de Martres, » Revue de Comminges et des Pyrénées Centrales, 111, 3.

- Cazes et al. 1999 D. Cazes, E. Ugaglia, V. Geneviève, L. Mouysset, J.-C. Arramond, Q. Cazes, Le Musée Saint-Raymond : musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse-Paris. p. 104-107

- Clarac 1841 F. Clarac, Musée de sculpture antique et moderne ou Description historique et graphique du Louvre et de toutes ses parties : des statues, bustes, bas-reliefs et inscriptions du Musée royal des Antiques et des Tuileries, et de plus de 2500 statues antiques … tirées des principaux musées et des diverses collections de l’Europe… accompagnée d’une iconographie égyptienne, grecque et romaine…. Tome II, Paris. p. 588

- Du Mège 1835 A. Du Mège, Description du musée des Antiques de Toulouse, Toulouse. no 140

- Du Mège 1828 A. Du Mège, Notice des monumens antiques et des objets de sculpture moderne conservés dans le musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. no 60

- Espérandieu 1908 É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, 2. Aquitaine, Paris. no 902

- Gachon 1926 P. Gachon, Histoire de Languedoc, Paris. pl. V, p. 72-73

- Godechot 1949 G. Godechot, Visages du Languedoc, Paris. p. 70

- Joulin 1901 L. Joulin, Les établissements gallo-romains de la plaine de Martres-Tolosane, Paris. fig. 121 B

- Lebègue 1889 A. Lebègue, « Une école inédite de sculpture gallo-romaine, » Revue des Pyrénées et de la France méridionale, p. 28. p. 9

- Massendari 2006 J. Massendari, La Haute-Garonne : hormis le Comminges et Toulouse 31/1 (Carte archéologique de la Gaule), Paris. p. 255, fig. 141

- Pagès 1867 F. Pagès, « La Vénus de Martres, » Revue archéologique du Midi de la France, 2, pp. 50–52.

- Pasquier 1985 A. Pasquier, La Vénus de Milo et les Aphrodites du Louvre (Albums), Paris.

- Pasquier, Martinez 2007 A. Pasquier, J.-L. Martinez, Praxitèle. Exhibition, Musée du Louvre, Paris, 23 March - 18 June 2007, Paris. p. 182-183, no 38

- Praviel 1935 A. Praviel, Toulouse : ville de briques et de soleil, Toulouse. p. 247

- Pugliese Carratelli 1997 G. Pugliese Carratelli, Enciclopedia dell’arte antica classica e orientale : secondo supplemento, 1971-1994, Rome.

- Rachou 1912 H. Rachou, Catalogue des collections de sculpture et d’épigraphie du musée de Toulouse, Toulouse. no 52

- Ramet 1935 H. Ramet, Histoire de Toulouse, Toulouse. p. 26-27

- Roschach 1904 E. Roschach, Histoire graphique de l’ancienne province de Languedoc, Toulouse. p. 211

- Roschach 1865 E. Roschach, Catalogue des antiquités et des objets d’art, Toulouse. no 52

- Slavazzi 1996 F. Slavazzi, Italia verius quam provincia : diffusione e funzioni delle copie di sculture greche nella Gallia Narbonensis (Aucnus), Naples. p. 41-45 et fig. 28

- Musée Saint-Raymond 2011 Musée Saint-Raymond, L’essentiel des collections (Les guides du MSR), Toulouse. p. 32-33

- Bulletin municipal Toulouse 1936 Bulletin municipal Toulouse, Bulletin municipal, Toulouse. pl. p. 605

To cite this notice

Capus P., "Head of Venus", in The sculptures of the roman villa of Chiragan, Toulouse, 2019, online <https://villachiragan.saintraymond.toulouse.fr/en/ark:/87276/a_ra_52>.